Jim Williams’ Smiling Faces: Exploring The Idea of Home As Self-Portrait

Art

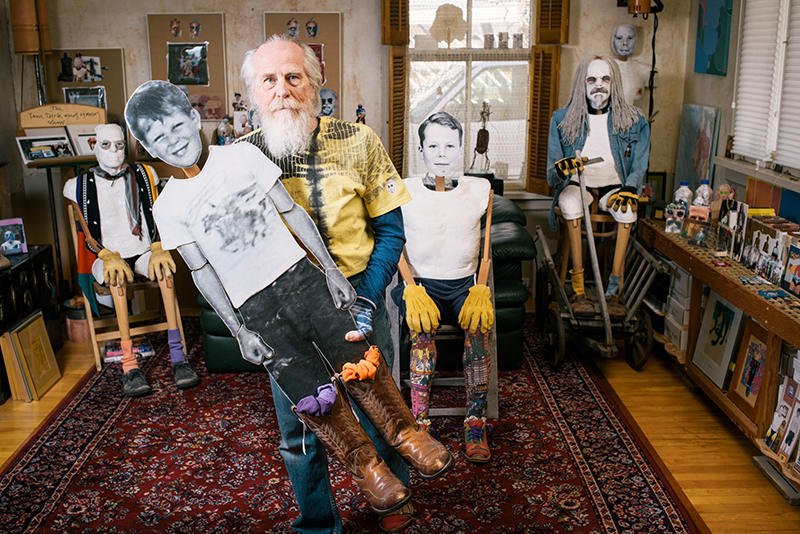

With its plain, white exterior, carefully kept garden and rock arrangements, and subtle deck railing, it looks like many other Avenues homes. Upon closer inspection, however, a magical world unfolds. It is a world filled with a thousand faces, plaster bodies propped up in chairs, alligator/human hybrids crawling along the ceiling, cowboys lurking in corners, Nostradomian scenes lining the floors, Junk Yard Dogs guarding the perimeters and finally, the home’s sole occupant, Williams: bearded, wearing Birkenstocks with mismatched socks, likely clad in a shirt featuring his own likeness, acting as the home’s protective sage. This is Home as Self-Portrait.

“For the last 25 years, I’ve been filling up the house,” says Williams, who covered every nook and cranny with his many surreal, pop art–leaned, multimedia works. In anticipation of an upcoming partnership with the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA)—which will feature a small installation in the museum’s foyer and, perhaps most compelling, free intimate tours of Williams’ home throughout the summer—Williams is unpacking every box and unwrapping every piece. Home as Self-Portrait is an archive show to celebrate a lifelong creative journey. “[This exhibit] is an accumulation of the shows that I’ve done over the years,” says Williams, but it’s also an act of closure. “This is not only the end of this particular art project—it is the end of me living here. It is the transition of many things.” With an impending move to the Portland area due to the fact that “I have three grandchildren and I love being around them,” says Williams, the artist is looking to leave a deep impression in the minds, hearts and eyes of his Utah audience.

Born in 1940, Williams is from a rural Kansas town. Yet despite his geographical isolation and his beginnings as “Kansas farmer stock,” Williams found solace in the counter-culture of the ’40s and ’50s with rock n’ roll and hot-rod cars. “Then the hippies came a long, and drug culture came along,” Williams says—a movement he was proud to be a part of. Williams attended the University of Wyoming and the University of Kansas in pursuit of an architectural engineering degree, after which Williams entered the cutthroat job market and found himself at odds. “I was dissatisfied with what I was doing in life. I quit my job and went back to where my parents lived,” says Williams. “That’s when—I’ll tell you honestly—I met my wife, I enrolled in art classes, and I had a friend living in Japan who sent me some pot in an envelope. I experienced all three of those within two months of each other. It completely changed my life.”

From there, Williams led a successful architecture career, but it didn’t satisfy his creative needs. With a sly smile crawling along his face, Williams says, “I kept all my creative juices for home—drawing, painting, photography.” Despite his creative proficiency, some of his work during the ’80s was not well received. Williams set a new trajectory for himself. “I said, ‘I’m gonna do paintings. They are gonna be colored; they are gonna be large; they are gonna have a theme,’” he says. This theme is the self-portrait. “When I am using myself as an image, it doesn’t change the work part of it—it’s still a graphic image; it’s still a project; it’s an artistic effort,” says Williams. “At some point, the question of narcissism comes up. It’s unavoidable, and I’ve kind of played with that,” even creating a trio of works called Narcissus Spring, Narcissus Creek and Narcissus Pond as a tongue-in-cheek nod to this criticism. “I think most artists do self-portrait or self-imagery,” says Williams, “whether they think they do or not.”

Cara Despain, artist, writer, friend of Williams and author of The Beginning of Now, a book chronicling Williams’ life and art, says, “[In Williams’ work,] you can trace influences from pop and art nouveau to the Pictures Generation, Fluxus and Dada.” In a 2011 show, Despain’s book and Williams’ work made a collaborative debut. “Now, with this exhibition with UMOCA five years later, people will finally get to come and see the work in situ,” says Despain, “[and hopefully] understand his home as a complete retrospective artwork and ultimate self-portrait.” As a somewhat solitary individual, Williams has had small, invite-only gatherings, but nothing quite as large as the UMOCA exhibit. “I’m justifying it now because after this [exhibition], it all goes in boxes—I sell my house and move,” says Williams. With some trepidation, he says, “This is people off the street seeing what’s here. There’s a vulnerability to that … I didn’t do this for them, but I’m doing this show for them to see it.”

In the future, Williams hopes to put his energies into sorting through 130,000 of his photographs and compiling zines. “I could do a zine about Tom, Dick and Harry,” he says, referring to a collaborative installation with friends and fellow artists Don Andrews and Marc Rodgers, “and a zine of my grandkids.” And to those individuals working on a creative project, Williams says, “I’d encourage you to keep at it, even if you throw it away or put it in a box. If you have a creative energy, satisfy it.”