Review: Pure Paint For Now People @ Weber State

Art

At first glance, a painting is immediately familiar. The art form is more quickly recognized than other forms of contemporary art, and so feels more approachable. When we hear the words “art” or “gallery,” our minds most often immediately concoct an image of a painting: a series of strokes on a two-dimensional canvas, perhaps depicting a still life near a window, perhaps portraying a well-dressed, unsmiling woman, and then hung with or without a frame on white walls.

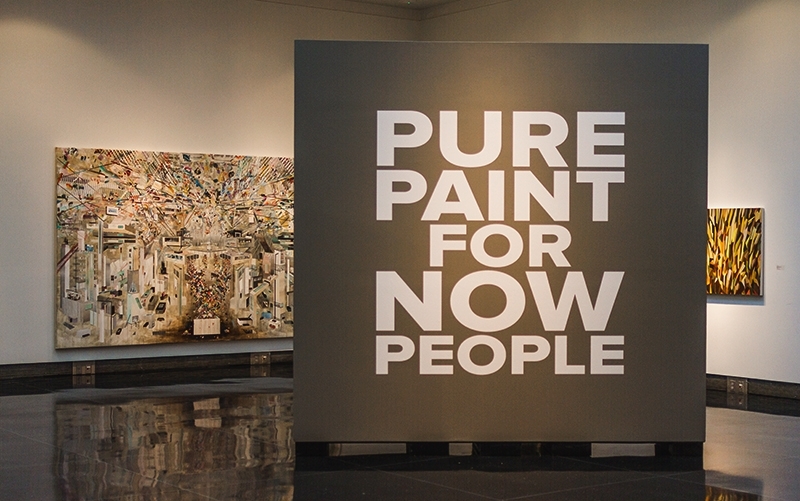

Pure Paint for Now People, the current exhibition at the Mary Elizabeth Dee Shaw Gallery at Weber State University, seeks to explore the definition of contemporary painting with a curated selection of pieces by locally, nationally and internationally recognized artists. The exhibition fosters bold statements for what the painting medium is and has become: a medium that has only ever needed to be concerned with redefining itself—both inward- and outward-looking; sometimes unorthodox, sometimes antagonistic; always alive.

The majority of the works selected for the exhibition are bright and vast, hung up on the walls of the exhibition and several standalone panels. One panel loudly proclaims “Pure Paint for Now People,” with the words “Paint” and “Now” emphasized. The eye-catching boldness of the paintings immediately appeals to our penchant for vivid color and intricate—but recognizable—composition. The colors range from bright pink to slate grey, and the strokes go from haphazardly piled on to meticulously geometrized. All of the paintings are contemporary. Some reflect the world as we know it; some glance into our futures, some reflect strong Modern influences; and some are contemporary simply because they were created in the present.

Caleb Weintraub’s “Spooky Action at a Distance” and Ricky Allman’s “Annunciate/Repudiate” provide skillful but unsettling expansions of what our future might look like. Weintraub’s painting greets us with a colorful depiction of large-eyed, alien-looking children who appear to rule a wild utopian jungle and its creatures. Allman’s painting of the future, on the other hand, moves away from nature toward a large, geometrized look at the hectic, inner workings of a futuristic city. Allman toys with and expands physical space, as well as psychological space, to create room for the possibility of new technologies and futures in viewers’ minds.

Other paintings seek to expand our perceptions of life now. In “Night Triptych” by Gideon Bok, the artist’s three panels of a hazy jazz café at night seek to recreate the sensations of the space. The people in the paintings play music or listen on couches, but certainly don’t sit still. As Bok paints, he follows the people’s movements, scraping out, painting over and overlapping the figures. In doing so, the artist creates a compelling, cinematic look into an inhabited space but incorporates subtle distortions of perception and time. Lisa Sanditz’s “Silverlake Reservoir” is a charming, illustrative investigation into American landscapes, both natural and built. Her painting of a quaint, far-off town with red rooftops and white buildings is set against a pink background. The reservoir is made up of a large mass of black, perfectly round circles that become smaller as they get closer to the town.

Several of the artists emphasize the process, working to expand or subvert long-established concepts and styles. Gianna Commito’s “Stow” uses pastel stripes to form large fragments. Her reinterpretation of the stripe moves the traditionally linear form to the illusory. Francesca Dimattio’s “Jacquard” incorporates the same patchwork quality and designs as does jacquard weaving, but in the center, Dimattio leaves a treasure: a thickly painted, pink-white flower. “RA: 15h 17m 31.29s DEC 31 ° 17m 31.618s,” by Blake Rayne, explores paintings as “signs”—works of fiction that provide cultural reference and are continually shaped by the contemporary landscape.

To explore how his painting is a sign, Rayne includes another type of loaded reference: text. In this particular work, Rayne plays with double entendres, writing “A WHOLE NEW SEASON OF LOST” to the side of a series robust squiggles. The meaning of the text and the lines then displace one another in viewers’ minds. In “Redact 035” by Max Presneill, the artist experiments by applying marks of paint and then negating them with further marks. The result is a shaded blue background with a series of bright shapes and squiggles, some more haphazard than others, on top of one another. Presneill uses the paint to experiment and reflect on what it means to have been “redacted,” even extending his process to such wide, contemporary scopes as the relationship of the people of interest to different authorities, government or otherwise.

Jennifer Meanley’s “Diatessaron” brings full circle these reinterpretations and revisions of painting. The work is a wide and gripping composition of paper collage and oil paint. Meanley’s cutouts, set against a black background, show fragmented faces and patterns of jewel-colored foliage. The figures on the left stand upright. Others are turned away from the viewer, hold a longing gaze or lie horizontally. The visual space, though fragmented, has a sense of rhythm and movement. There’s a call-and-response to the work, a sense of the artist’s continual building, disintegration and rebuilding. Most importantly, the figures in this space bring us back to the basic experiences of human existence, though in a reimagined way. Meanley seeks to give weighted expression to love, longing, fear, affection and the many ways in which human beings foster closeness, intimacy and connection.

The beauty of this exhibition lies in its optimism and surefire belief in painting. The exhibition doesn’t breach boundaries, but it doesn’t seek to. Rather, it reminds us of what paint is and can be. The medium continues to reinvent itself and its realities. It moves from broad movements to simplified palettes to cluttered spaces. It drips, blends and layers, sometimes exposing the colors and canvas behind. It is a medium for experimentation and representation, inquiry and discovery. The exhibition’s title, “Pure Paint for Now People,” emphasizes “Paint Now,” which can be understood both as an imperative and as an indication of the contemporary time period. The words that remain, however, describe the most critical, and human, aspect of what painting is: “Pure for People.”

Pure Paint for Now People is on exhibition at Weber State University’s Mary Elizabeth Dee Shaw Gallery until April 10. Admission is free. For gallery hours and more information, visit the exhibition website.

You can also check out Talyn Sherer’s stunning gallery of pieces from the exhibit, only on SLUGMag.com!