Six Artists: BDAC’s Summer Gallery

Art

Click images for captions

I’ve been to the Bountiful Davis Art Center (BDAC) many times, but this particular gallery opening felt special: the streets were adorned with chalk from the chalk festival, and children and adults were celebrating art with caricatures of Lightning McQueen or Rapunzel. It was a warm Friday night, one of those soft Utah nights that hint at true summer. As those nights of heat near, BDAC offers six new exhibitions that explore abstraction, mediation, color and more.

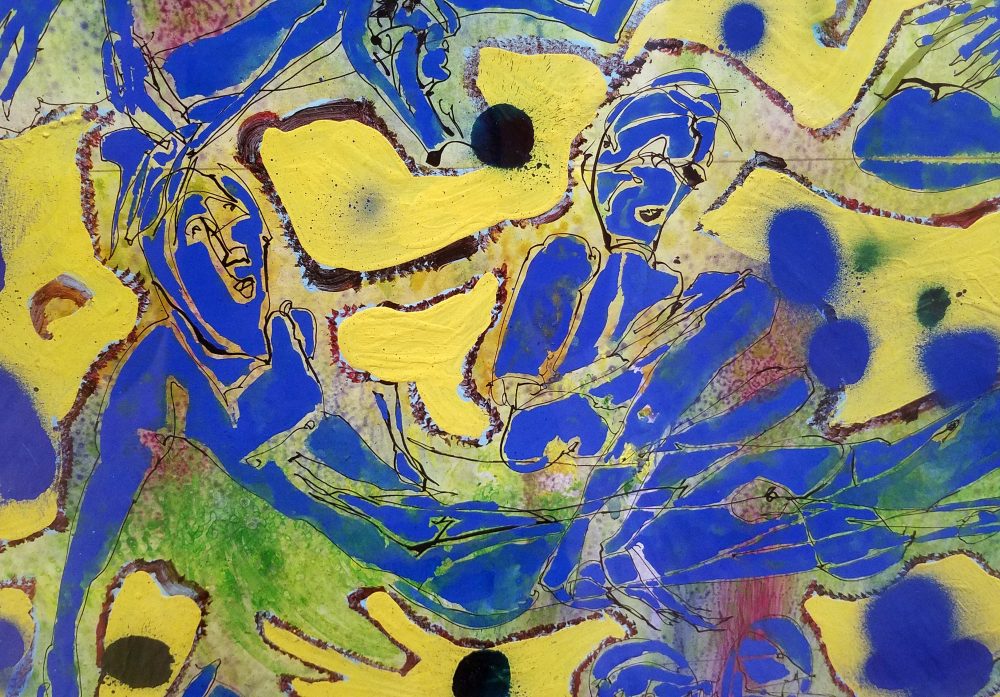

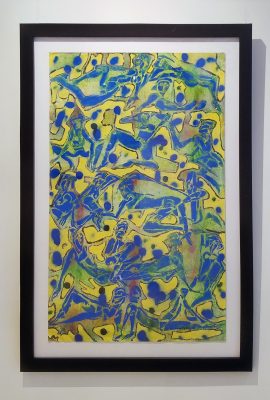

In the main gallery is An Outsider Looking Inward, a showing of several pieces of art by the late Charles Keeling Lassiter. Lassiter broke from popular abstract expressionism in the ’50s and became renowned in his own right, but today a big part of what frames his works is his agoraphobia, an anxiety disorder that few of us know much about, but about which much is assumed. Lassiter’s paintings and drawings are colorful and diverse, often depicting human-looking shapes and structures in perspective using complementary colors. The abstractions often feel anthropomorphic, such as in “Blue Group Reclining,” where it almost looks like a group of blue figures are having an orgy, holding each other and bent across one another. It’s messy and incongruous, but to me it’s there, and with Lassiter’s work I often felt this tendency to lay my ideas of agoraphobia down as a lens for his work. Knowing as little about the phobia as I did, I couldn’t help but want to see a longing, a meditation on solitude as well as socialization. “Waking Brain” depicts a man looking at his audience; he seems shirtless, and his gaze is unnerving. Lassiter’s best works—such as this one—shake you out of your ability to pathologize his art.

This is a sharp contrast to Oonju Chun, whose show Ignition shares the main gallery. “My paintings are totally devoid of meaning from its creator,” Chun says. “The emotional response is direct and immediate.” It’s true, and you can ease your strain to connect with art just by looking at Chun’s work. A painting like “Big Fifth I,” for instance, instantly draws you in by not requiring anything from you more than the moment you decided to look at it. Chun makes work that looks erratic but holds a sense of calm—it’s a rawness turned into something visual and there’s something comforting about knowing that you can trust how you feel about something. A piece like “Linger,” in which most of the painting is offset by a large, black void overlapping many suffocating colors, may have the capacity for a robust reading, but there’s something to be said for looking at a work using intuition alone.

Lastly in the main gallery is The Heritage of Mankind by John Mack. “My intention is to invoke curiosity,” Mack says. “The objects may appear familiar yet have instilled in them a sense of mystery as to their purpose and identity; stimulating the imagination and hopefully forcing us to think beyond what we know.” These curious objects are large and punctuate the gallery, a sort of way to pull you in and out of other works with their knowing alienation. “Probe 82012” is a spiny satellite while “POD 1051882” almost looks like a large, homemade steel bomb. They’re strange artifacts with whimsy and polish, and as you move between Chun’s fluttering paints and Lassiter’s fascinations, it’s impossible to avoid the strange allure Mack creates.

Annexed from the main gallery is Leslie D. Pippen’s Choose to See a Car Accident, Snake or Owl. These simple paintings of flowers and sunsets and back porches with UFOs are mediated by hundreds of small, translucent beads sitting flush on the paintings’ surface, and the effect is that the work reflects a different light, channeled into a grid of plastic pixels. “Eclipse in Totality 2017” is my favorite: a large portrait painting of a watermelon and a plant, the sun above sprinkling down drops of yellow that form the background. Up close the watermelon looks simple, colorful but unremarkable. It’s once I step back, then forward and back again, that I see how much odd vitality is added by the beads. “Plastic is the material of modern mechanical reproduction and the legacy of human distancing from nature,” says Pippen. “It is quite possibly the residue of a creature that has outgrown its incubator and exhausted the yolk.”

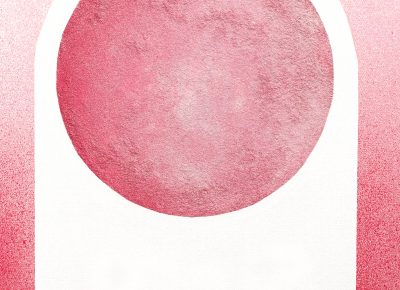

The last two showings are in BDAC’s underground gallery. Amy Fairchild and Havoc Hendricks share the space, and Fairchild’s minimalist and color-focused Color My World pairs nicely with Hendricks’ focus on clean shapes and lines in Moons & Mountains. Fairchild spent most of her young life in Germany, but after graduating from Westminster, she found herself exploring color through photography. “Striving to remove the complications of daily life into a morphing form of pure color is what I pursue,” she says. The photographs are calming and hazy, though pure in color, and they play off any light sources near them. Seeing myself reflected in them and their soft hues was comforting, and I liked holding up my camera light to them to see the way each would react. Hendrick’s pieces don’t play with light, but their minimalist, graphic design–esque nature slots well with Fairchild. “Mountain Install” looks three-dimensional but isn’t, which is a simple illusion of its cascading line work and flowing color. “Moon Arch Blue” and “Moon Arch Pink” both sit together, two pieces that also focus on one color and use it to draw your eye across the acrylic.

You can see each of these exhibitions through June 22 at BDAC, 90 N Main St. 10–6 p.m. Tuesday through Friday, and noon to 5 p.m. on Saturdays. Visit bdac.org for more information.