Three curators at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts decided to navigate the usage of words and text in art and to showcase the versatility and artistry of language, particularly when it is used in works of art. So, they put together [con]text, an exploration of how visual artists have harnessed the power of language.

Illustrate, Illuminate: [con]text @ UMFA Exhibit

Art

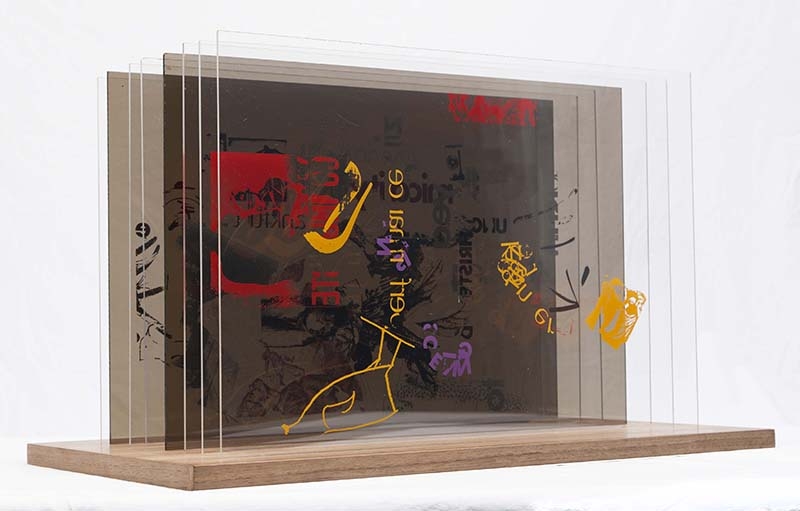

John Cage (American, 1912–1992) and Calvin Sumsion, Not Wanting to Say Anything About Marcel, Plexigram VI, 1969. Screenprint on acrylic panels with wooden base. Purchased with funds from the National Endowment for the Arts, Associated Students of the University of Utah, and the Charles E. Merrill Trust.

Words, text and language are regularly viewed as separate entities from art. The word “art” evokes thoughts of works on display in an art museum, meant for personal scrutiny and understanding. Text, however, is confined to those small plaques next to the artwork that provide platforms to better understand the pieces: context, information about the artist and time period, an expert’s analysis of the piece. That small section of text remains straightforward and objective, no matter how perplexing or inscrutable the art it describes may be.

Three curators at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts decided to navigate the usage of words and text in art and to showcase the versatility and artistry of language, particularly when it is used in works of art. So, they put together [con]text, an exploration of how visual artists have harnessed the power of language. The exhibition opened Friday, Dec. 19, and, in tandem with UMFA’s strategic plan, spans over 50 works from UMFA’s impressive permanent collection—many of the works hadn’t been shown for years, or have never been on exhibition. The show was curated by Annie Burbidge Ream, Assistant Curator of Education for public school programs and statewide outreach, Luke Kelly, Associate Director of Antiques, and Whitney Tassie, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art.

The exhibition is made up of a total of five adjacent rooms, or thematic groupings. On the wall of each, an evocative word is written along with its definition to provide different lenses through which to look and understand the art. The words chosen were wonderfully suggestive: “communicate,” “relate,” “entice,” “advocate” and “illuminate.” This yielded a seemingly eclectic and enormous diversity of works in terms of time period, origin, intent and medium. The thematic groupings were comprehensive and easy for visitors to grasp—seeing as we are practically bombarded by words and text in our everyday lives—and the exhibition felt remarkably cohesive. It also made a point to interact with its audience. Several plaques with descriptions of the work also included a few questions to prompt the viewer into thinking further about what they are seeing and perceiving. By the end, we recognize the malleability and subjectivity of text as a form of expression, particularly within the context of visual art.

In the first room, we are introduced to the broad theme of “communicate.” Visitors are greeted by a Japanese depiction of a fish, painted so that it is strikingly similar to its written Kanji counterpart. A lithograph by David Goines showcases a serif typeface and the geometries of the letters of our alphabet. At the center is John Cage and Calvin Sumsion’s 1969 collaboration, “Not Wanting to Say Anything About Marcel, Plexigram I-VI,” which features a series of six out of eight sets of screen prints on Plexiglass. There are eight individual sheets of acrylic in each set, colorfully printed with incoherent text and fragments of images. Within each set, the panels are placed upright so that visitors can look through them, but the order of the panels is at the discretion of whoever put together the work. These Plexigrams were meant to honor and remember Duchamp after his death, and Cage chose to use a complex mix of color, type, space and chance to speak volumes about a dear friend—just with no explicit words.

The curators focused on the day-to-day for “relate”: how we use language in our ordinary lives as a way to connect to and understand one another. Americana linocuts, with detailed, comic-style illustrations and lyrics from American folk songs, are mounted near French political cartoons. Selections from Marcellus Lauron’s “The Cryes of London” offer viewers a slice of street life in 17th Century London. Each piece is a simple but cleverly detailed illustration of some street hawker and what that individual might be barking at passersby (things like “Get your eggs here!” and so on). Below is audio featuring University of Utah Theatre students and employees of the Marriott library performing what these street hawkers may have sounded like, replete with heavy English accents and background sounds.

Andy Warhol’s signature Campbell’s soup can was featured in the “entice” room. To its side are clear plaques. When visitors hold up the plaques to frame a work of art in front of them, they see that advertising slogans are printed on the plaques. Funnily enough, Campbell’s soup becomes even more of a tongue-in-cheek comment on a capitalist and consumerist society when it reads, “Now half the calories!” underneath.

“Advocate” focused on strong, sometimes glaring, politically driven works. On the right wall are Bruce Nauman and Shannon Ebner’s respective inquiries into the palindrome “raw war.” While both seem to exhibit a hinted condemnation of war, they also comment on the type of language that fuels a war and pervades during wartime. On the center wall was one of the most popular pieces of the exhibition, Willie Cole’s 1993 piece, “How Do You Spell America? #8.” The enormous chalkboard is mounted with “AMERICA” written neatly across the top. Under each letter is a long list of words that begin with that particular letter. Full sentences can be read across: “A marginally effective remedy is commercially approved.” When read vertically, the piece sounds more musical, more poetic: “Allover American amazing America always are a another a abandoned any awareness adding after.” The artist toys with words that read together like verse or like a manifesto of sorts, yet he also decries America in the ironic context of a schoolroom.

Throughout these first few rooms, several never-before-seen selections from Robert Rauschenberg’s “Surface Series from Currents” hang on the walls, tying together multiple thematic groupings. Here, Rauschenberg simultaneously communicates, relates and advocates. He captures the times with black-and-white screen prints based around collages and clippings from the New York Times, the Chicago Tribune and so on. Rauschenberg emphasizes certain headlines to show the turmoil of the 1960s, with anti-war marches, corruption and drug usage.

The final room was certainly my favorite: “illuminate.” Here, visual art supplemented words, whereas mostly the opposite was true for the rest of the exhibition. Lawrence Weiner’s phrase, which is owned by UMFA, now no longer reads across a corner in enormous blue text. Rather, the curators made the phrase, “Bent to a straight and narrow at a point of passage,” into temporary tattoos for visitors to take and keep with them. We read printed poetry by Tony Towle, all written about Lee Bontecou’s process and artistry, which was paired with Lee Bontecou’s etchings. Selections from Robert Motherwell’s visual pairing of color with Rafael Alberti’s “A La Pintura” stunningly take up an entire wall. Here, Motherwell pairs sparsely spaced lines of poetry—colorful text for the Spanish lines, black text for the translated English—with blocks of slightly embellished color. Alberti’s poetry enchants, delicately skirting topics like the color azul, passion and sensuality, lines and letters. Next, we witness how different artists can interpret the same work. Salvador Dali’s vivid, bleeding, painted illustrations for Alice in Wonderland differs drastically from depictions for the same text by Yayoi Kusama, or an Aboriginal author, or a pop-up book artist. A typewriter for visitors to leave messages is paired with photographs from Ed Ruscha’s Royal Road Test, in which the artist throws a typewriter out of a moving car. On the typewriter’s paper feed, someone had written, “when in the face of all human kind we try to.” Others decided to leave their mark: “madi was here.”

[con]text is exceptional because it explores a very real part of our lives: language. The exhibition navigates numerous interpretations and usages of text in visual art, and it does so in a way that emphasizes interaction, education and engagement. Each of the pieces offers new aspects of the back-and-forth between visual art and text without offering a concrete conclusion. Rather, the works lead us to recognize that words can be just as subjective as any other form of art, and they evoke an appreciation of language for its fluidity and dynamism.

The Utah Museum of Fine Arts is located on the University of Utah campus in the Marcia and John Price Museum Building at 410 Campus Center Drive. Free admission is offered the first Wednesday and third Saturday of each month. [con]text will be on display through Jul. 26, 2015. For more information, visit the museum website.