Selective Nature: Nancy Rivera

Art

Sitting on a table in Nancy Rivera’s modest studio in the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA) are three green vases on a paisley-patterned, silk-like paper that’s emerald green. In the vases are flowers that are delicately and methodically arranged but somehow still erratic to the eye—perhaps because they’re synthetic, completely artificial, or perhaps it’s their relative foreignness to each other, each flower from a season and even biome that would normally preclude their existence together. In any case, the flowers look perfectly real. They require no maintenance. They are beautiful, unique—and could only realistically exist as fakes.

These arrangements are a component of Rivera’s residency at UMOCA, after which her work will be displayed through this August. The vases are a purposeful appropriation of the work of 18th century Dutch painter Jan van Huysum, well regarded for his still-life paintings of flower arrangements. Because Huysum’s paintings were composed of flowers imported from all over Europe and Asia, the paintings would take years to create, ultimately becoming composites of flowers that had never actually occupied the vase at the same time. “Now it’s the year 2018 versus 1727,” Rivera says. “I have the ability of going online and order the exact same flowers that he used to create those arrangements, except they’re all synthetic.” It flips the thought on its head: What was fake is real, and what was real is now fake.

Of course, it was always fake. Van Huysum made paintings, and Rivera takes photographs. But the point is to steer you down that line of thinking. Most art is “fake” under a certain definition, but that subconscious moment of choice, a lightning strike between boundaries, is exactly what keeps Rivera chipping away at the concept. The pieces bring Van Huysum’s ideas into not just the contemporary current but also the landscape around us. “We are surrounded by nature,” Rivera says, “but within that world we still have things that we construct that we still call nature.” As an example, we discuss lawns: We curate them, mow and preen them, taming their growth. And maybe it’s not that deep—a lawn is a lawn—but undeniably it’s also a preference for a certain order, a patch of the wild for decoration. Rivera is asking about those assumptions, those ones we make about our relationship to the natural world, and what that designation means: its value and, when we inevitably alter it, how and why our perception of its value changes.

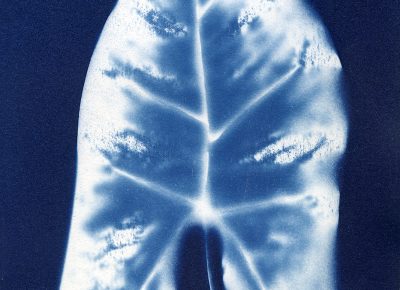

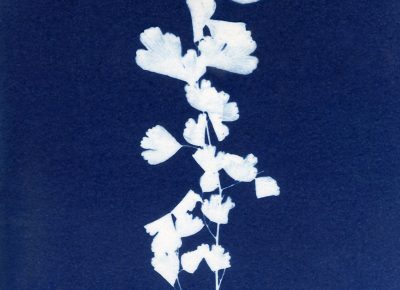

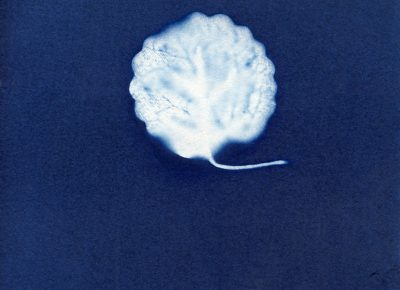

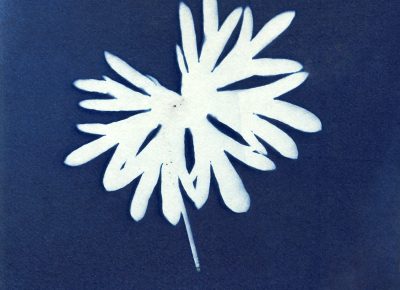

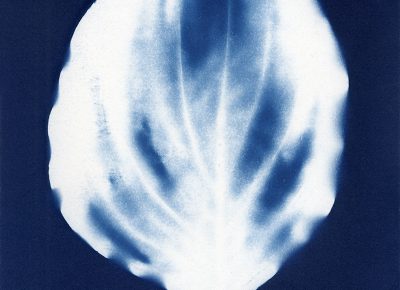

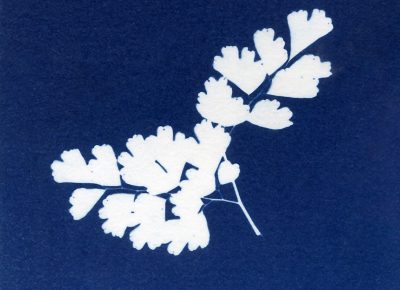

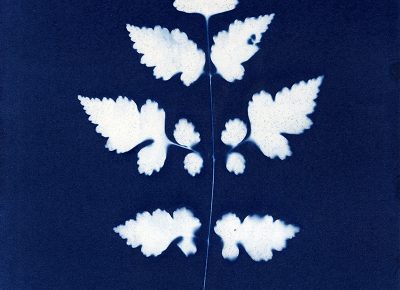

Rivera has wrestled with this boundary of the real since her days completing her MFA at the University of Utah. Her work centered around the cyanotype processes, a cameraless form of photography that exposes a photosensitive iron solution onto a surface and then dries it in a dark room. (The name cyanotype comes from the color of the resulting images, which are shades of light blue, cyan.) This was the process of the first recorded woman photographer Anna Atkins, who was trained as a botanist and photographed plants for her own scientific reference. Rivera plays off Atkins’ work as well, creating cyanotypes of flowers both synthetic and real, and the finished product makes the difference near indistinguishable. “It’s very hard to see which one’s real and which is artificial,” she says.

Though blueprint-like, the cyanotype destabilizes our perception of the camera as the origin point of the photograph, challenging our reliance on a perceived natural order. Rivera’s use of craft materials works similarly. “In the late ’70s, early ’80s, artists were still debating what was considered ‘contemporary fine artwork’ versus ‘craft,’” says Rivera. “A lot of artists started creating things like embroideries, quilts, that type of thing, that’s usually thought of as a ‘craft’ but incorporating it into a contemporary art context, bringing it into the gallery, has people look at it and say, ‘This is art.’” From here follows Rivera’s vases and synthetic arrangements, which, beyond their high-level conceptual wringing, are aesthetically very pretty. You could even call them beautiful, though Rivera characterizes that as reductive to contemporary art.

“I think people minimize ideas,” Rivera says. “They see, for example, the cyanotype pieces … and they’re like, ‘It’s beautiful!’ … That’s something you really have to push [the audience] into thinking more about. Some people are more open to it than others, and it’s fine. Art is supposed to be fun to look at and something that’s appealing. All art in some way is inherently … beautiful? I hate to use that word, but there you go.”

Rivera’s family emigrated from Mexico when she was 12. “I just stuck around,” she says. We both agree there’s a calmness to Salt Lake in comparison to other, larger cities. But one of the things that bothers her is the relatively small amount of space given here to contemporary art. “We have one contemporary art museum and a couple of contemporary galleries … sometimes I just want to see things and get inspired by other people’s work … going online and looking something up, it’s not the same as going into the gallery,” she says. “I’m seeing the work. It’s such a different experience. I think Salt Lake lacks that, and that’s my only complaint about the city.” I ask her if she thinks things are improving. “I think there are a lot of people who are trying to make a change,” she says. “There’s Luminaria, who are a photography studio who’s doing alternative and contemporary photography work, and that’s really exciting. But we used to have Central Utah Art Center—I used to work at CUAC just before it closed, and it’s just disappointing to see places like that leave.”

Later that weekend, after our interview, I mowed my lawn, but before I did, I noticed my compulsion to do it, to bring it into a feeling of order. It’s a moment that usually passes unnoticed. That evening I bought some flowers, some real ones, and put them in a vase, and I tried not to think ahead to the inevitable day when I would throw away the dead thing.

Nancy Rivera’s four-piece exhibition opens in UMOCA’s A-I-R Space on Aug. 3 and runs through Sep. 1. For more information, visit utahmoca.org and find Rivera on Instagram as @_nancy_rivera.

Editor’s note: The bouquet arrangement of “After Jan van Huysum: 2” was previously uncredited. It has been updated with credit to Mia Atherton.