The Fall of Gondolin

Book Reviews

The Fall of Gondolin

J.R.R Tolkien

HarperCollins

Street: 08.30

In the forest of dreams, there stands a hobbit. He bears a terrible burden—the Ring of the Abhorred, a closed circle from which there is no escape, a prison for all the wills and fates on this mortal earth. Before him is an ancient, elven queen. Men call her a witch, the gods a rebel, but here she is a cosmically tragic figure. Her many millennia weigh heavily on every word she says, and meanwhile, the Ring calls out to her. It tells her that if she were to claim it, to make the expedient choice and force her will upon enemies and friends alike, she could save her home, her people, herself. As she wrestles with this temptation, she says to the hobbit, “Ere the fall of Nargothrond or Gondolin I passed over the mountains, and […] through ages of the world we have fought the long defeat.”

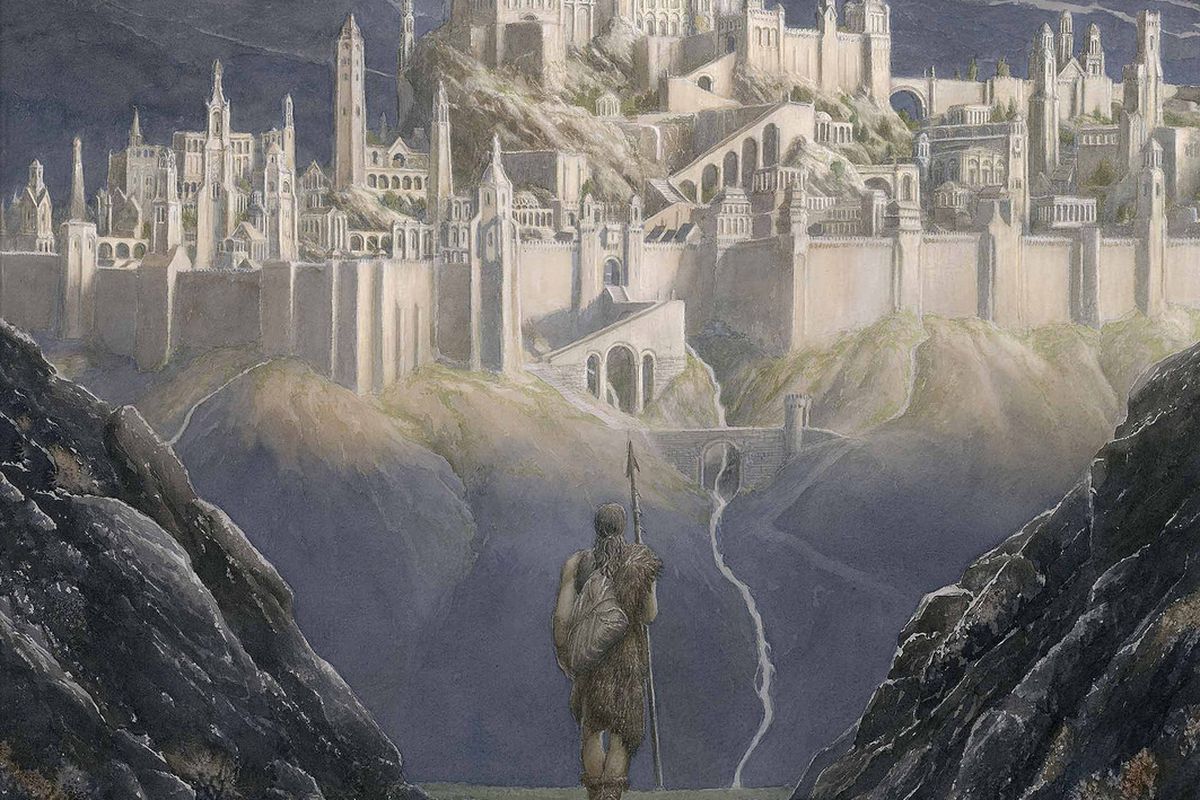

Like Galadriel’s final surrender to the mortality of Middle-earth, The Fall of Gondolin by J.R.R. Tolkien, published Aug. 30, 2018, is the final entry in Christopher Tolkien’s long career of publishing his father’s previous drafts and essays. Like 2017’s Beren and Lúthien, Gondolin is a collection of previously published drafts with added commentary. These regard the fall of the city of Gondolin, or Hidden Rock, the last of the elven strongholds to withstand the demiurgical hegemony of Morgoth, Sauron’s master and Middle-earth’s Satan. The elves that live there are the last of those that, valiantly and foolishly, dared the judgment of the gods to seek their own vengeance against the Enemy. If the name of this volume didn’t give it away, they do not find that vengeance.

Let’s dispose of the recommendation first: If you’re not interested in reading a narrative presented in a series of only moderately different drafts, then it’s difficult to recommend Gondolin. If you want to read of the titular fall but aren’t interested in the supplemental material, read pages 145 to 201 and then from the first full paragraph on 50 to 111. This method takes the highly detailed final version and adds on everything it’s missing from the first version. It’s interesting to compare these two drafts. The first—and only complete—version was written when Tolkien was 24 years-old and on sick-leave during WWI. It contains a raw but unmeasured passion that moves the narrative in poignant but staccato bursts. I find it particularly fascinating to read descriptions that are clearly Tolkien’s first attempt to communicate his imagined trainset. Take for example the orcs, whose “hearts were of granite and their bodies deformed; foul their faces which smiled not, but their laugh that of the clash of metal.” The final version was written 35 years later, when Tolkien was working on Lord of the Rings and hoping he could get the Silmarillion published in the same volume. This depicts the meditative, melancholy wanderings of protagonist Tuor up to his arrival at Gondolin, and is the more masterfully done. Of particular note is Tuor, along with his companion Voronwë, hiding from orcs and huddling “side by side under the grey cloak […] and pant[ing] like tired foxes.”

If you’re undecided, then the question naturally becomes “what is special about The Fall of Gondolin?” At first glance, its central event—the siege of a great city of stone by the archonic agents of a tyrant—seems almost cliché within the setting. The sieges of Helm’s Deep and Minas Tirith dominate the military narrative of the Lord of the Rings and have the benefit of being writ-large on film by Peter Jackson. Why should you want to read the same basic setup divorced from the context of Frodo’s quest to destroy the Ring? Three reasons suggest themselves.

First is the difference in scale. The Lord of the Rings is set in the Third Age of Middle-earth during which magic and legend are explicitly fading to make way for the world to come—ours. By contrast, Gondolin is set in the First Age, a mythic age where the elves were nearly gods themselves and the Enemy so mighty that he once tried to make all of existence his body. The siege of Gondolin stars heroes who make up for their lack of character arcs with deeds of bardic renown, balrogs by the hundreds, great serpents of flowing steel and even armored transport vehicles for the orcs. Even the peremptory language of the first draft is enough to capture the horror and majesty of Gondolin’s fall. If you’re given to fantasy as a genre, Gondolin is a feast for the imagination.

Second is the key difference between the sieges of Gondolin, Helm’s Deep and Minas Tirith—in the latter two, the heroes win. Not so at Gondolin. Gondolin, well, falls, and in its ruin countless elves perish, their culture is shattered and Morgoth’s victory over Middle-earth is complete. Yet Gondolin is, at its core, a story about hope—hope unlooked for and unprepared. Imagine if Sauron had recovered the Ring and destroyed Gondor and Rohan and harried the elves to their boats, and held total dominion over Middle-earth. What hope would exist then?

That question takes us to our third reason and back to Galadriel’s lament of the “long defeat.” The Fall of Gondolin, like nearly all of Tolkien’s legendarium, is about mortality. Against an enemy as absolute and merciless as time, there can be no victory. Gondolin was always going to fall, as did the European empires in WWI, as will all our personal conceits when death inevitably finds us defenseless against its ultimate authority. All ambitions fail and all monuments crumble. Again, what hope is there?

As the wheel of mortality crushes us under its tread, so, too, does it raise new generations. When the people and dreams we love are warped and destroyed, at that same time, new people and dreams arise. Gondolin’s hope was never in strength of arms or purity of purpose, but in one child rescued from its ruin. The Fall of Gondolin seems an especially appropriate fairy tale for today, when our country and culture often seem on the verge of imploding, and climate change promises catastrophes to dwarf those concerns. Sometimes it feels like the noose gets tighter every day. Sometimes it feels like there’s no point. But every day you get up and fight—for yourself, your loved ones, what you believe in, is another day you give your hopes a chance to be realized. Even if you die, as you surely will, with your hopes unrealized at the time of your death, they do not die with you. Even the very cynical cannot see all ends, and even when the last bastions of truth and justice fall, truth and justice live on.

Aurë entuluva! Day shall come again!