The Art of Salts Science

Art

The artist Motoi Yamamoto’s presence at Weber State University was observed through an unorthodox panel celebrating his medium—salt. Traditionally, lectures given on artists’ exhibits I’ve seen tend to follow a fairly standardized pattern of explaining the artist’s backstory, translating the emotions from the installment or piece and concluding with a personal impact statement. What happened at the panel was, instead, an avant-garde celebration for a substance I had never considered as anything more than a way to mask the actual taste of most foods I consume. The panel consisted of several professors from Weber State University and Westminster College, as well the acclaimed culinary leader on salt, Mark Bitterman.

The panel started with Bonnie K. Baxter, a Professor of Biology at Westminster College, explaining to the audience what a halophile was while pulling up a PowerPoint presentation with images of microcosmic pictures of salt compounds—and I got nervous. The idea of needing a short list of vocabulary terms before proceeding, almost terrified me. After all, science isn’t art, salt isn’t science—salt is salt, so I thought. The amount of time I spend thinking about salt daily is reduced to nothing more than my arm’s muscle memory at every meal. This night was dedicated to salt though, and I was completely unprepared for the massive amount of information I was about to receive. Baxter continued to share her vast knowledge on the biology of salt, primarily organisms that enjoy, want and need salt to survive—halophiles. Following suit with Baxter’s talk on the life in salt was Michelle Culumber, who spoke about the aforementioned halophiles’ role in genetic transfer (evolution) and element recycling. While Baxter’s presentation focused on the halophiles themselves, Culumber’s covered the complexity of salt and halophiles’ roles in the “Tree of Life.” She also, rather casually, threw a comment or two on pathogens surviving the brine of Great Salt Lake.

I’ve never consciously observed the relationship between the Great Salt Lake and the people of Utah. I would guess that this in part comes with the fact that I’m simply accustomed to its presence and have developed a certain clutter blindness to its assault on my senses while commuting. Dr. Carla Koons Trentelman shared the complexity of the Great Salt Lake’s relationship with the people of Utah with a certain amount of romanticism, ranging from its rooted history stemming from the Great Depression to the present anomalies such as property value on a salt lake vs. a fresh water lake.

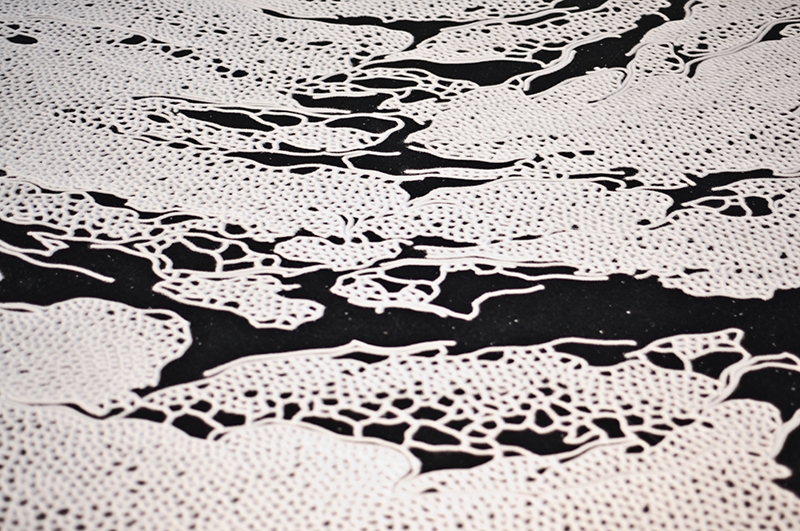

Earlier in the night, moderator Paul Crow briefly shared Yamamoto’s story, and his simultaneously tedious, methodical and meditational process of creating his salt-masterpieces inspired by memories of his deceased sister. Hikmet Sydney Loe, an Art History professor at Westminster, shared examples of artists who also use salt to create their pieces, or have pieces depicting salt in part or as a whole. Robert Smithson, most known for his earthwork sculpture, Spiral Jetty, was discussed as well as artists Tacita Dean and Holly Simonsen. Deans anamorphic film JG was filmed on Utah’s saline landscapes as well as landscapes in Central California. Simonsens’ work is so closely tied to the Great Salt Lake that in 2010 she circumnavigated the shore, over a hundred miles, as part of her poetic journey.

I would have to say I couldn’t have been more pleased with speaker Angelika Pagels’ presentation on the seemingly modest household staple, the salt shaker. This historical presentation included the cultural significance of salt itself, beginning with extravagant vessels used to signify the status of the table head, and were presented in a manner that truly showed off the rarity of the salt. An example of such saltcellars is Benventuo Cellini’s “Saliera,” which is currently (and not so modestly) valued at $60 million. Pagels’ oration also explored colloquial idioms and a variety of superstitions involving salt, including an explanation as to why it’s bad to spill salt (an omen of betrayal or broken bargain) and why the remnants are to be thrown over the offender’s left shoulder. Blame that pesky shoulder-riding deity, the horned devil, which tends to show up on the left shoulder. She also shared pictures such as Da Vinci’s “Last Supper,” which shows Judas spilling the saltshaker, and other historically relevant paintings that boasted saltcellars.

The final speaker of the evening was Bitterman, a man who literally wrote a manifesto for salt (Salted: A Manifesto on the World’s Most Essential Mineral with Recipes). His passion started with a simply made steak in France. He has since traveled the world collecting various salts and opening a store that specializes in finishing salts. While Bittermans accomplishments in the culinary world are countless, I say, the highlight of his career is the luxury of being able to enthusiastically suck on a Himalayan salt block in a room full of people and still manage to be one of the most admired individuals present, with no one questioning his sanity. The evening closed with Bitterman discussing where to buy the finest salts in Utah—Tony Caputo’s Gourmet Food Market and Deli, he says—as well as providing the opportunity to taste a sampling from his own collection.

While the format of the evening was unconventional, I was tremendously enjoyed the overall atmosphere and flow. Beginning with the science and structure of salt as a component in the ecosystem allowed the audience to reconsider the significance of the substance. Revealing cultural and artistic ties with salt as the night progressed, I couldn’t help but recognize that salt isn’t just salt at all. The event provided a refreshing approach to dissecting an art installation with the focus on the literal medium—a topic that allowed the audience to revise ordinary, table-spice subject matter into something far more complex than ever imagined.

On April 12, starting at 10 a.m. the community is invited to gather up the salt used in Yamamotos’ exhibition and return it to the Spiral Jetty in the Great Salt Lake.