James Whitaker Brings an AI Apocalypse into Focus in Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die

Arts

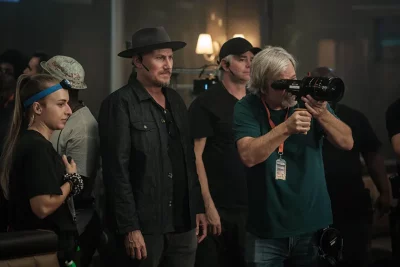

James Whitaker has spent his career finding the emotional truth inside genre filmmaking, grounding ambitious ideas in images that feel tactile, human and lived-in. A cinematographer whose work favors atmosphere over flash and character over spectacle, Whitaker brings that sensibility to Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die — a darkly comic science fiction time travel story — shaping a film that balances satire, science fiction and uneasy realism. Long before he was designing the look of an AI apocalypse with director Gore Verbinski, Whitaker was a kid sneaking horror movies after bedtime and biking to nearby film sets just to watch cameras roll — an origin story that still echoes in the way he approaches every frame.

“I grew up sort of in the Chicago area, and I just was obsessed with movies from a really young age,” Whitaker says. His relationship with cinema began not as a technical pursuit, but as an emotional one. Sneaking out of bed after his parents fell asleep, Whitaker would turn on a small TV and watch whatever he could find, “Hopefully horror that would scare the hell out of me and make me really feel… what it feels like to be a human being,” Whitaker says. At the same time, iconic director John Hughes was shooting teen comedies such as Ferris Bueller’s Day Off just miles away on Chicago’s North Shore. While his friends chased auditions and background roles, Whitaker was the kid asking where the cameras were. “I just wanna go ride my bike down to set and watch them shoot,” Whitaker says. Filmmaking felt distant and mysterious, but irresistible.

That curiosity was fed by access. Whitaker got a hold of his father’s Super 8 camera and was constantly shooting both moving images and still photography. It wasn’t until college — after completing an economics major — that Whitaker knew what he wanted to do with his life. Film classes followed, and then a migration to Los Angeles in the early 1990s, where Whitaker cut his teeth in music videos for Radiohead and The Black Eyed Peas. The mix of instinct, craft and self-discovery informs his approach decades later, particularly on a film that asks big questions without abandoning its humanity.

From a technical standpoint, Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die was carefully designed to support ensemble storytelling. Whitaker and Verbinski settled on the ARRI Alexa Mini LF, framing the film in a 2.40:1 aspect ratio from the outset. Extensive testing was done with the Alexa 65, inspired by the large-format intimacy that Lawrence Sher achieved on Joker. “We really loved what happens in portrait mode,” Whitaker explains, noting the emotional closeness that a shallow depth of field can bring. But this film wasn’t about isolating individuals — it was about groups. With characters often arranged in horseshoe-like compositions, all needing to remain clearly identifiable, the Mini LF proved the better choice. The Alexa 65’s extreme falloff, while beautiful, risked turning practical staging into a technical liability. Those choices were inseparable from the film’s themes. Although the film is a satire — Whitaker cites Dr. Strangelove as a tonal touchstone — he and Verbinski were committed to realism as a baseline. “We’re really not interested in breaking from reality for as much as possible,” Whitaker explains. That philosophy shaped the opening at Norm’s Diner, which Verbinski wanted to feel unmistakably real: bright, evenly lit and free of shadow. “You can’t hide in there,” Whitaker says, emphasizing how the lack of visual cover reinforces the audience’s initial suspicion of Sam Rockwell’s character. He might be crazy, homeless or dangerous — but nothing about the space suggests artifice. As the story expands outward — from the diner through kitchens, hallways, basements, alleys and an abandoned shopping mall — the realism persists until it can’t. In locations where reality offered no plausible light sources, such as the powerless mall, Whitaker allowed the imagery to drift into something more mythic. Moonlight filtering through architecture, car headlights slicing through darkness — these moments bend realism without breaking it, signaling a shift in perception rather than a wholesale departure from the real world.

That balance culminates in the room where it happens: AI super intelligence is invented by a mysterious young boy played by Artie Wilkinson-Hunt. The space feels alien despite existing within a house, and designing it required extensive testing and experimentation. How do you light an environment that represents not just a machine, but a subjective journey through time and space? The answer emerges gradually, through a visual language that contrasts sharply with the grounded diner that opens the film, yet feels like an inevitable extension of the same reality. Lenses played a crucial role in achieving that cohesion. Whitaker chose Panavision Panaspeeds, working with Dan Sasaki, the Vice President of Optical Engineering at Panavision, to find glass that wasn’t overly perfect. Shooting in large format demanded careful attention to edge focus, especially in group shots, but Whitaker wanted character in the image. The Panaspeeds were subtly detuned — just enough to introduce warmth and texture without sacrificing control. Their lineage, closely related to the Primo lenses Verbinski used on Pirates of the Caribbean, made them a natural fit. “We presented everything to Gore, and he loved it,” Whitaker says.

In a film that warns of the dangers of the illusion of perfection through technology, imperfection becomes a virtue. Whitaker’s cinematography resists slick futurism in favor of something tactile and human, reminding the audience that even the most abstract threats ultimately land in real places, whether it’s a Norm’s Diner in Los Angeles on a weeknight or inside the darkest recesses of the mind.

Read other film interviews by Patrick Gibbs:

Noah Wyle’s Direct Approach to The Pitt Season Two

How Louis Paxton Came into his Own with The Incomer