Track History, Tell Stories: Michael McLane on Literature, the Environment and Social Justice

Art

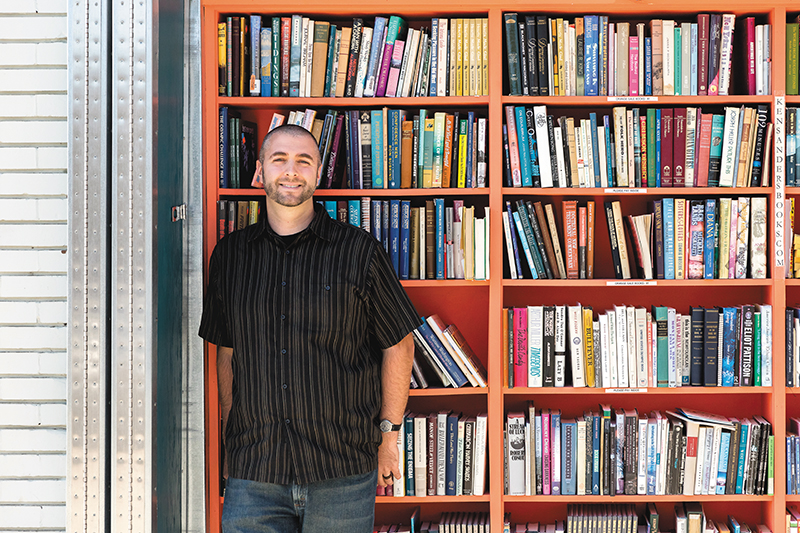

In the heart of Ken Sanders Rare Books, past the weathered manuscripts and “Hayduke Lives!” T-shirts, sat poet, author and editor Michael McLane. The Downtown antiquarian bookshop is a historical and cultural epicenter and, since McLane’s undergraduate career, “the most important part of my literary education,” he says. McLane engaged with filmmakers, historians, polygamists and, of course, Ken Sanders, the “incredible storyteller” and friend of Edward Abbey. McLane’s time with Sanders propelled his fascination with the Intermountain West, though he didn’t discover his literary relationships with Utah’s wild and cultural landscapes until after he attempted parting with them.

While working on his MFA at Colorado State, McLane “craved the tension between the culture and subcultures,” which undammed a personal flooding of Utah and Mormonism into his poetry. After grad school, McLane returned to Utah and to Ken Sanders, also working for the Utah State Archives. There, McLane photographed boxes of letters former Utah Governor Rampton sent to families of Vietnam War victims—basically, a local death toll. “Eventually, those numbers crash down on you,” says McLane. But they gave rise to a “long series of poems, which begin as a cohesive, narrative-form letter from Governor Rampton—the letter begins to break down, eventually to the same kind of emotional breakdown I had.” McClane embraces these seemingly ordinary experiences in “the poet’s endless drive to create meaning”—such as his work at an aerial survey company, which etched “aerial maps of the city and national parks” into his work.

Historically and culturally diverse experiences led McLane to use storytelling and poetry to highlight social justice issues pertaining to “the intersection of human processes and how they’re detrimental to the environment—and to us.” He later graduated from the University of Utah’s Environmental Humanities graduate program and looks to the North to describe his research thesis. “I was driving past the Beck Street area one night and smelled the sulfur from the springs. The sights, sounds and smells took me back to being a kid,” says McLane. His father was a Union Pacific Railroad man who often let McLane tag along. “There was always fire, sparks and steam,” he says, reimagining the aerial view of the railyard from the loud, six-story railroad tower, competing only with the encroaching refinery for tallest structure.

The untold stories and forgotten history of Beck Street’s 170-year-old past have become McLane’s rabbit hole. The refinery hub was formerly Warm Springs, “a focal point for recreation.” With surrounding neighborhoods on all sides, it’s now overrun by some of the most toxic industry in the valley. “I’m tracing the history of how that happened, trailing the multi-cultural history from the Native American tribes to the Hawaiians, LGBT community and the Mormon pioneers that run into my own family,” says McLane. He is publishing a personal and environmental non-fiction book next year, as well as a book-length poem about the Warm Springs/Beck Street project.

While the Warm Springs project is personal, “it’s engaged in a much larger story,” says McLane, one that aims to galvanize the community to preserve it. Like McLane, many people are turning to art therapy to construct metanarratives about social, political, and environmental tensions. Since the 2016 presidential election, McClane has noticed a rise in poetic engagement, which “acts as a guide for people to interact during times of war and turbulence … [a] zeitgeist that turns people to something more lyric,” he says, and to literary communities in general. As a contributing review editor for Sugar House Review—a local, biannual poetry journal—McLane works to provide such platforms: While strictly poetics, Sugar House Review is topically expansive, allowing for a wide range of crucial conversations and growing increasingly popular as more people turn to poetry in lieu of prose.

McLane is also an editor for saltfront: an environmental humanities journal rooted in “the stories of humans in the places that they live,” says McLane. Salt Front publishes work by local, national and international artists in fiction, nonfiction, poetry and photography aimed at “examining human ecology, the myths about climate change and that maybe we’re not OK, and where do we go from here?” says McLane. Rather look for outlets to publish creative environmental humanities work, McLane and other former EH students simply created one.

Sugar House Review and saltfront are necessary “acts of love” for McLane. His day job comprises running the literary program for Utah Humanities—particularly its annual, month-long book festival, spanning 20 towns and 120-plus events. McLane helps cities statewide determine which authors and topics to bring into and benefit their communities. “This is a social justice move for event planners” like McLane, he says. “I can’t speak for everyone, but I think more disenfranchised voices are being heard now, and it’s imperative for them to be able to engage the world.”

These types of programs and communities drive the dialogue between writers and the public. From Ogden to Cedar City, he commends folks like Abraham Smith and Marcy Rizzi for being community assets and advocates for local writers. “Utah isn’t a flyover zone anymore,” he says. “It’s a literary hub.” The demand for direct engagement is growing, but requires that individuals support independent bookstores and libraries. They are “the heart of communities,” and the locomotion for transforming our voices and stories into tangible change.

Find some of McLane’s work at saltfront.org, sugarhousereview.com and utahhumanities.org.