From Script to Set: Janice Chan on Designing for Theater

Performance & Theatre

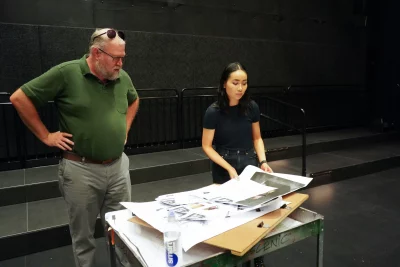

Many folks working in “the theater” have a self-professed, life-long passion for the performing arts, but that’s not the case for scenic designer Janice Chan. “Growing up, I was never a theater kid,”

Chan says. She stumbled into this profession while attending advertising classes at Utah Valley University, which felt too corporate for her. Theater offered more creative expression, and she fell in love with the community aspect of the practice.

Chan believes that “a successful design is when no one element stands out,” and her process is heavily intertwined with other departments. She believes establishing a relationship with the full team is critical and loves working with her friends and colleagues at UVU. She says of this collaboration: “You’re not trying to outshine anyone else, and everyone working toward that one mission is really important.”

Upon receiving the script for a production, Chan begins discussions with the director and the rest of the production team (namely the sound, costume and lighting departments). The success of the show design hinges on this collaborative effort to ensure that all departments are consistent and come together as a whole. “We’re all trying to achieve one goal,” she says. That group needs to determine the mood and the type of story they want to tell. Understanding the audience is another crucial piece—knowing who they are performing for and how to connect and engage with viewers.

“You’re not trying to outshine anyone else, and everyone working toward that one mission is really important.”

Next, she dives into the research phase, sourcing as many world-building materials as she can, from the architecture of that era to the socioeconomic dynamics. Her goal is to be as authentic to the time period as possible. From there, she comes up with a design mission statement that stems from the director’s concept, which becomes the guiding principle through all of her visual design choices.

Finally, it’s time to start sketching out the sets. Chan uses a Computer-Aided Design (CAD) program to layout all of the sets virtually. When that’s finished, she hands them off to the technical director and shop builders who actualize the pieces. A few weeks before the show opens, the production runs a tech week, where they get to see it all onstage with the actors. The whole design process typically takes about three months from start to finish

“I love that the audience becomes very involved in the show itself … You look across the stage and you see the audience members sitting. You’re in this experience together.”

Chan loves surrealism, saying this movement “is more truthful than realism itself, in trying to capture that authentic human experience.” Though often limited by a predetermined venue, she loves working “in the round”—a theater venue in which the audience surrounds the stage—and in other unconventional spaces. “I love that the audience becomes very involved in the show itself,” she says. “You look across the stage and you see the audience members sitting. You’re in this experience together.”

One of her favorite productions to work on was The Laramie Project (The Noorda Center for the Performing Arts, January 2019), a play about Matthew Shepard’s tragic death. This was an immersive audience experience, inviting attendees to move with the cast throughout the set, turning them into active participants in the story. For her senior project at UVU, Chan designed the set for Urinetown: The Musical (The Noorda Center for the Performing Arts, September 2019). A satire about capitalism, she approached the design through the lens of Dadaism, the original anti-art art movement. The set was her interpretation of a playground, featuring shape-shifting structures that were reassembled in different configurations throughout the performance.

Chan has several projects currently in the works. Next, she’s designing a set for UVU’s production of The Diary of Anne Frank, which will open this October at Bastian Theatre in Orem. This will be followed in November with Hansel and Gretel, an opera presented by the UVU Department of Music, which opens in November 8 at Smith Theatre in Orem. Finally, she’s working on Balthazar, an original piece produced by Plan-B Theatre in Salt Lake City, opening at Rose Wagner Theatre on February 15, 2024.

Read more on local theatrical productions:

Play Review: Murder On The Orient Express

SLAC’s Summer Show: A Beautiful Day in The Neighborhood