The Executioner’s Song Screening and Panel Discussion @ The Salt Lake Library

Community

For good or for ill, Gary Gilmore is an international pop icon.

From Nike to The Adverts, the hands of Gilmore have touched the psyche of the world. Gilmore was convicted and later found guilty of robbing and murdering a hotel clerk and a gas attendant in a two-day stretch. What makes Gilmore’s case so interesting on the surface is that when the courts sentenced him to the death penalty, he actively pursued his execution, rather than appealing it. At the time, there had been a moratorium on executions (introduced by the Supreme Court) in the US for nearly a decade and Gilmore’s case reopened the practice of executions.

Last Friday, the Utah Film Center and the Norman Mailer Center held a screening and panel discussion about The Executioner’s Song, a made-for-TV movie about the brief period surrounding Gilmore’s murders and subsequent execution.

Over the past months, I have become acutely familiar with the Gilmore case, ingesting books, articles, songs and tomes surrounding Gilmore’s life. Before I go into the film screening, a few things need to be cleared up:

1. Gilmore was no sympathetic character. Gilmore was indeed a product of an abusive environment, but that does not excuse him from the multiple violent acts he engaged in during his life, which include child molestation, rape and multiple assaults. The movie seems to gloss over his past and case facts just to make Gilmore more sympathetic.

2. Gilmore’s and Nicole Baker’s relationship was not romantic. They were two mentally unhealthy people with difficult upbringings. The film acknowledges this but proceeds to frame their story in a classic movie love story.

3. The number of people who sensationalized Gilmore’s trial is astounding. All of those who profited from the coverage of his crimes should be ashamed of themselves. They are, in my opinion, responsible for the non-stop coverage of monsters like Jared Loughner, James Homers and Jerad Miller. Schiller and Mailer’s book, while captivating, provocative and culturally reflective, involved themselves in the story, intentionally hiding facts for their book and hounding victims on both sides of the crime. This wasn’t journalism, this wasn’t a creative expedition, this was profiteering—picking at the bones of a tragedy.

Overall, the book and film incompatible. Both are considered lengthy for their respective mediums, but the movie fails to capture the entire storyline, even if it is nearly three hours. The movie focuses on the relationship of Gilmore and Baker, and the events leading up to the murders, then jumps to execution of Gilmore. The book itself is a factual and detailed summary of Gilmore’s life and his crimes, of passion focusing on different aspects of Gilmore’s life and lives around him. For native Utahns, the film is a throwback to when Utah had more in common with Wyoming than it did with Colorado. I spent a lot of time trying to spot film locations and thinking how the areas have changed, starting with the empty nothingness that once surrounded the Point of the Mountain prison and the farmhouses along Geneva Road.

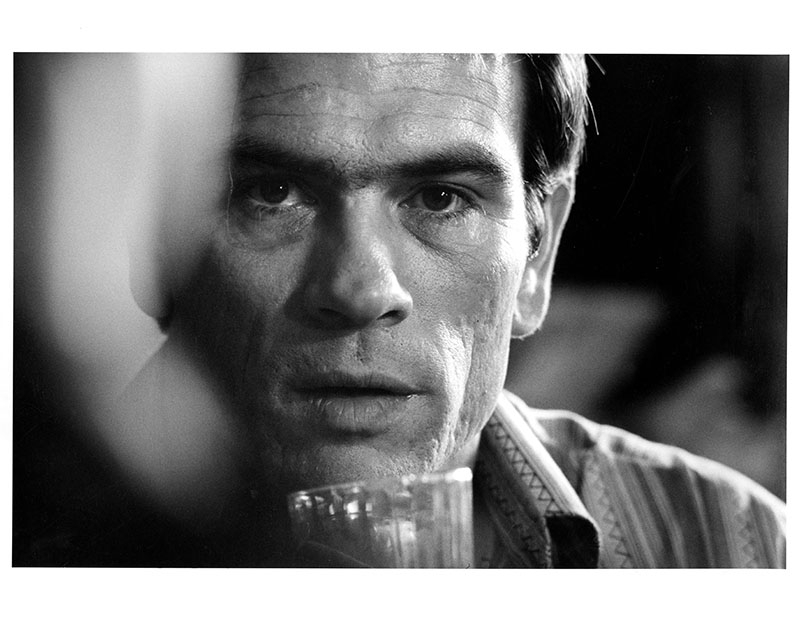

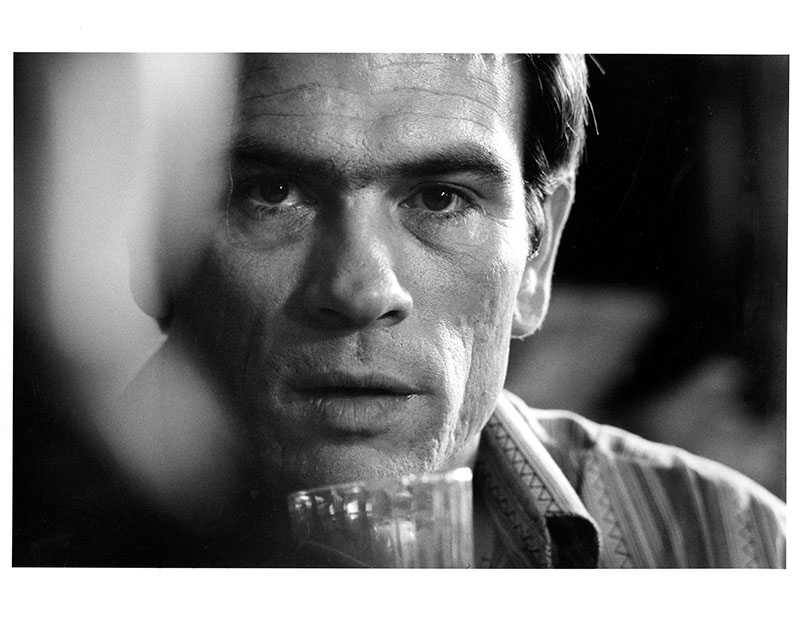

Gilmore (played by Tommy Lee Jones) and Baker’s (played by Roseanna Arquette) live an existence of desperation and constant trouble. Baker is 20, on her third marriage and has two children and Gilmore (age 35) has spent most of his life between correctional facilities. The couple quickly fall in love and begin an unhealthy relationship dominated by Gilmore and his childish whims. Eventually Gilmore commits the two robbery/murders in Utah County in an attempt to make a payment on a truck. From there, the story focuses on Gilmore’s decision to not appeal the death penalty, his control of Baker while inside prison and the profiteering from his story.

The movie closes with the state-sponsored murder of Gilmore (the first person to be executed in the US in nearly a decade), leaving the audience with a bitter taste in its mouth, asking itself if the death penalty is a moral punishment. While the film is over-the-top in the first half, Jones’ portrayal of Gilmore is dark, intelligent and sympathetic, which saves the movie from its overemphasis on the romantic relationship of Gilmore and Baker.

A panel discussion sponsored by the Utah Film Center followed the movie. The panel consisted of Lawrence Schiller, director; Vern Anderson, former editor at the Salt Lake Tribune; Bill Beecham (absent), former Bureau Chief of the Associated Press in Salt Lake City; Tamera Smith Allred, former reporter at the Deseret News; and Robert Moody, attorney, with Anderson moderating the panel.

The first topic came from panelist Bill Beecham, who asked Schiller if he influenced the authorities in their allowing Schiller to be the sole journalist witnessing Gilmore’s execution. Based on the tone of the question, it was clear Beecham was still sore on Schiller’s influence on Gilmore and his lawyers. The room felt tense as the first topic challenged Schiller’s integrity as a writer. Schiller, at first stumbling in his speech, admitted to influencing Gilmore and his lawyers, but denied any attempts on his part to influence the judges and officials.

Following the palatable tension, the other speakers introduced themselves and their role in the Gilmore case. Tamera Smith Allred, the most interesting member of the panel, described her experience as being a journalist in her early twenties on the bottom rung of the Deseret News, who found herself covering the Gilmore case after she developed a relationship with Baker, having met after a court proceeding. Allred outlined her relationship with Baker, saying that up until recently, she had not talked to Baker for more than two decades, but had recently met up to discuss their lives. According to Allred, Baker has moved past the Gilmore case, had more children and spends her time being a grandma and gardening.

The panel then answered questions from the audience. Questions from the audience varied from issues like the early-Mormon concept of Blood Atonement, the stories of Gilmore’s victims’ families and how both the film and book depict the Intermountain West. The most interesting statement, for me, came from Moody, who exclaimed that he never forgave Gilmore for what he did to his two victims (Max Jensen and Ben Bushnell), however he found Gilmore to be pleasant and extremely intelligent. To be frank, the conversation was interesting, but there was nothing new revealed or subjects dealt with in detail due to the hour length restriction. It was people treading statements they’ve made over the years, I really wished there would have been a second hour of discussion so the panel could dive deeper into the nitty-gritty of the case, their personal feelings on state sponsored murder and how the case can be related to our modern obsession with lone wolf shooters and serial killers.