DesignBuildBLUFF: Collaborative Homebuilding in the Navajo Nation

Activism, Outreach and Education

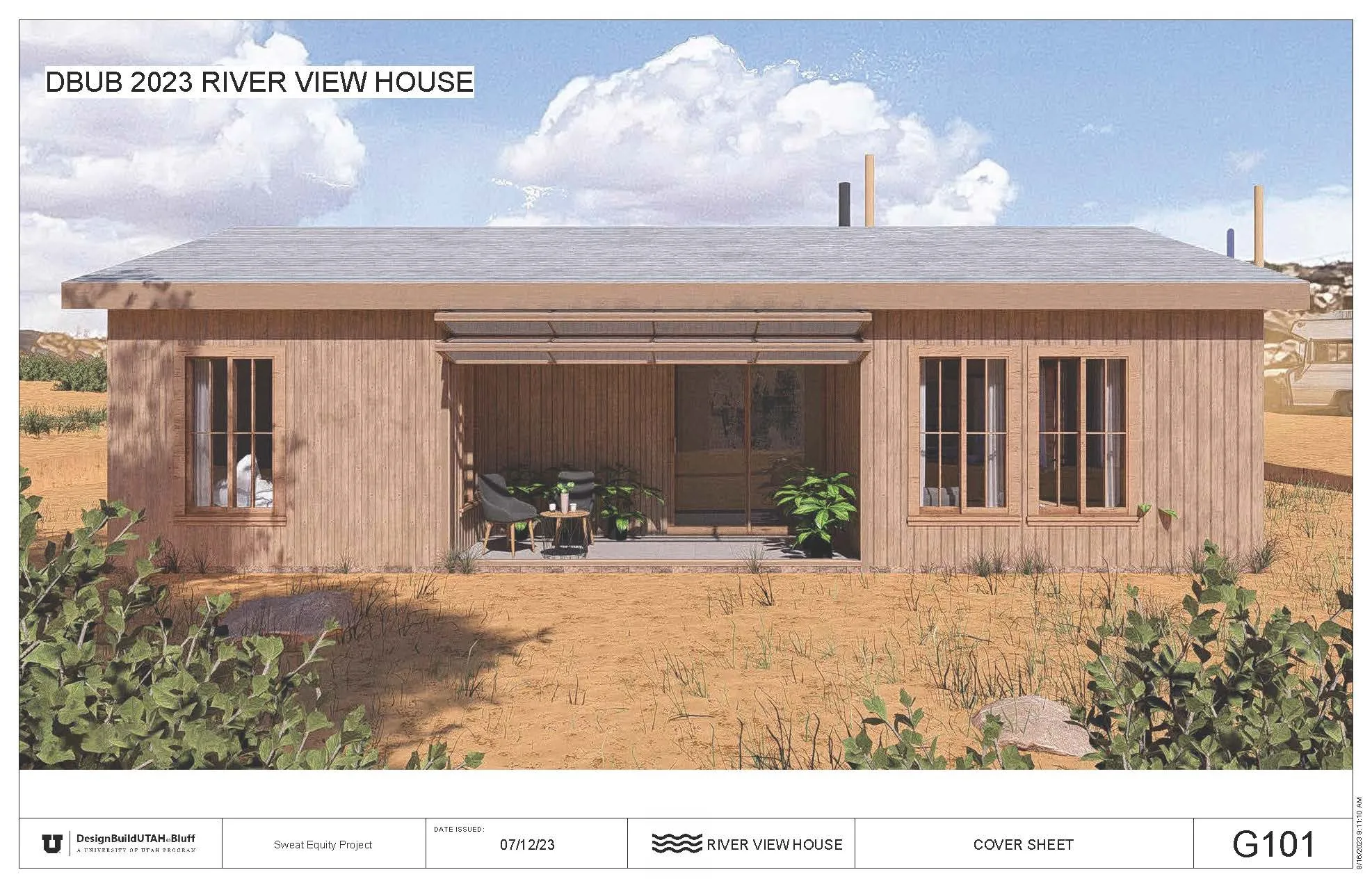

It’s a five-and-a-half hour drive from Salt Lake City to Bluff, Utah. The Wasatch Mountains give way to farmland, which softens to desert dust, and as you pass into southeastern San Juan County, the towns shrink and the houses sprawl. Tucked among the tall mesas that rule the landscape is the town of Bluff on the tip of the Navajo Nation. Each semester, University of Utah’s DesignBuildBLUFF architecture students arrive to Bluff with one goal: to design and build a home in just 12 weeks.

The new homeowners, tribal leaders, local children and countless visiting volunteers help to make the task possible for the students. No construction experience is needed, only a collaborative spirit. “The design process can be an educational opportunity for everyone,” says DesignBuildBLUFF Coordinator Hiroko Yamamoto.

“The design process can be an educational opportunity for everyone.”

DesignBuildBLUFF was founded by Hank Louis in 2000 and has connected graduate-level architecture students with the town ever since. Louis found that there were many development projects in Salt Lake City while rural, Indigenous communities facing poverty were often overlooked. It was also harder for residents to access building materials due to their remote locations. DesignBuildBLUFF allows students to gain on-the-ground experience vital to their career search while creating and designing builds with a tangible, immediate impact on their beneficiaries.

Bluff residents apply for the program, and one family is chosen each semester to receive the finished build. Students design the sketches and layout of the new home over a semester in Salt Lake City, developing the concept and schematics, creating sketches and preparing construction documents. They also speak to the home recipient and study southwestern and Indigenous architecture. The group of students then move to Bluff for the following semester where they will immerse themselves in gaining new perspectives and knowledge from the Navajo community.

For Yamamoto, cross-cultural study experiences have been the most meaningful of her career. As a student in Japan, she joined hands-on programs all over the world. After going to Bluff as a student in the program, her passion for her work reignited. She quit her job at a design firm in Tokyo to stay on board with the architecture program. Yamamoto and her husband Atsushi now coordinate DesignBuildBLUFF together. They hope to inspire a new generation to embrace the community-building aspect of design.

“The most important thing is how much the homeowner attaches to the new house so they can … pass [it] to the next generation.”

When it comes to the design itself, sustainability is a major priority, and although solar panels and recycled materials appear in the builds, preservation is the main emphasis. “The most important thing is how much the homeowner attaches to the new house so they can … pass [it] to the next generation,” says Yamamoto.

Clients are intimately involved in the construction and building process which helps them to connect with their new home and ensures they’ll take care of it for years to come. DesignBuildBLUFF calls this concept “sweat equity” since the client is sweating alongside the workers. “We always encourage the homeowner to show up as much as they can,” says Yamamoto. “Then by the end of the semester, they know the material, they know the tools, and … they can take over the tasks in the future.”

The homes use materials that are simple, local and accessible. This makes them much easier to maintain. Some techniques, such as making mesa bricks, are basic enough that even children can take part. It’s an older, lo-fi approach to sustainability, but it’s proven successful for over 20 years. When the builds are finished, they look at home in the landscape. “Earthen material presents … the beauty of the Navajo land and it kind of represents their culture,” Yamamoto says.

“Earthen material presents … the beauty of the Navajo land and it kind of represents their culture.”

Architecture can seem daunting to the inexperienced. For Yamamoto, though, design is something in which everyone can take part. She compares it to cooking a meal—an architect at a big firm will present their build to the client like a chef would a meal at a restaurant, but DesignBuildBLUFF takes a different approach. “Our idea is more barbecue style,” she says. “Everyone can bring some food items, and we cook and eat together.”

You can learn more about DesignBuildBLUFF and check out their past work at bluff.designbuildutah.org.

Read more about local community-building efforts:

Sowing Seeds of Stability With New Roots SLC

Sweet Hazel and Co.’s Community-Oriented Approach to Vegan Creations