Free The Fridges: Salt Lake Community Fridges

Community

Sarah Balland, Johanna McAllister and Izzy are quick to correct the notion that they are leaders for Salt Lake Community Fridges (SLCF). Balland, McAllister and Izzy each play a vital role in the project’s existence, but they work alongside many others to maintain community fridges that are free to use and contribute to. “Food insecurity is caused by [industries that have] hierarchical structures, and these are structures that we avoid recreating,” Izzy says.

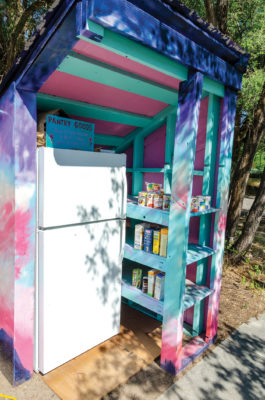

SLCF is an offshoot of SLC Mutual Aid, which in Balland’s words “is a collective-building, anti-capitalist resilience [org.] facilitating mutual aid projects and practicing community care.” Strengthening community is the cornerstone philosophy that this collective lives and breathes. SLCF focuses on addressing food insecurity in a dignified and autonomous way through direct community involvement. There are three community fridges in the SLC area, and each are hosted by everyday people within the community. Inside these fridges you will find freely available food items for anyone to use, open 24/7 and filled by neighbors, friends or anyone else who wants to redistribute their own resources.

“People need to be involved in the decisions for their own community.”

Food insecurity is not a new problem. In a world with an abundance of food and resources, the root of this problem is evidently profit-driven. Food is commodified and becomes wasted when it cannot be paid for. Balland, McAllister and Izzy all touch on the absurdity that food has become something certain industries would rather throw away than use to freely feed people. Ballandaffirms that “access to food is a human right,” and McAllister adds that within the bedrock of a right to food is a person’s right to exist.

Izzy points out that profound change is possible through organization within our own communities. One goal of SLCF is to “shift minds conceptually toward a world that works for everybody. In order to have a new world, you have to build it, and it’s not as scary [as you may think],” says Izzy. McCallister offers the ethos “solidarity not charity,” which is another cornerstone of SLCF. It’s the concept that we all take and give. Charity is a traditional system of sharing that can actually disempower communities by creating imbalanced power dynamics between those with and without resources. “People need to be involved in the decisions for their own community,” says Izzy. One can use the fridge whenever they’d like, fostering an autonomy of choice. This allows one to choose to stay anonymous or to connect with their neighbors. “The fact that [the] fridges are being used justifies their existence,” says Balland. Community members are proving that food is a human right through their reciprocal participation. Moreover, they are growing their communities’ dedication to others’ wellbeing.

“Food insecurity is caused by [industries that have] hierarchical structures, and these are structures that we avoid recreating.”

SLCF is one of many organizations helping address food insecurity and other systemic issues. For example, Rose Park Brown Berets fights against gentrification and displacement. Zoning, redlining and single-family homes can create “food apartheid” zones and increase food insecurity. These mechanisms force people to travel farther to large corporations for food, over time creating a dearth in food access in neighborhoods that may already be underserved. Carry the Water Garden is an Indigenous garden that helps provide food access as well. “Demystifying the act of organizing is important,” explains Izzy. There are hyper-local ways to address deep, societal issues and it starts on an individual level. “It’s important for everyone to acknowledge their role in their community,” says Balland.

To get involved, SLCF encourages community members to slide into the DMs on Instagram @slc.community.frigdes. There, you can find fridges, sign up to help maintain and coordinate fridges, start your own fridge or learn more about the initiative. Venmo donations are accepted at @saltlake-mutualaid (donation name: “freedges”).

Read more on local food:

Urban Micro Farming: The Story of Lincoln Street Farm

Around the World In 7 Grocery Trips