Review: Celeste

Community

Celeste

Matt Makes Games

Reviewed on: Nintendo Switch

Also on: Steam (PC and Mac), Xbox One and PS4

Street: 01.25

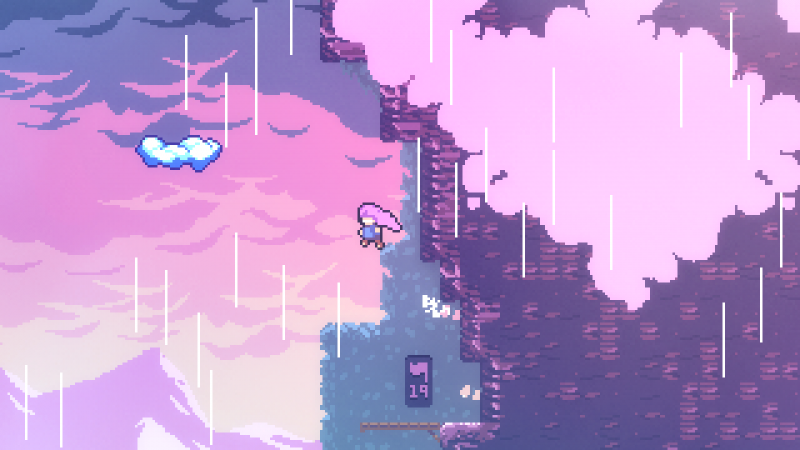

It is not easy to conceive of yourself as a realistically flawed person. Adulthood is less a challenge of coming into the age of responsibility, more the challenge of increased awareness and self-perception. Celeste demonstrated this to me in a way I wasn’t necessarily prepared to feel, and it made for a very frustrating and reflective game. Each time I played and fell down a pit or crushed into spikes, I wanted to perform better. When you begin the game, you play as Madeline climbing the titular Mt. Celeste, and you’re committed to completing this task over anything else—Madeline’s desire is unshakeable. She has never done this before. She doesn’t know how to climb a mountain; all she knows is that she must do it—that if she does this one thing, she’ll find some inner peace.

What she lacks in experience, Madeline makes up for in a mysterious ability, allowing her to jump and dash fixed distances in any of eight directions: up, down, left, right and diagonally. You can dash once per jump, and it resets once you touch ground. Madeline can also grip to walls and jump off them. Madeline is nothing if not capable, but the task of climbing Mt. Celeste demands the complete extension of all her abilities: precise timing and aim, a grasp of momentum and space. The difficulty works toward an end, though. What makes Celeste transcendent among its peers is how its gameplay and emotional arcs fit the same journey, how illness, health and triumph can all occupy the same space.

Structurally, Celeste is a series of over 700 rooms that ascend toward the top of a mountain. The game initially feels one-note. In Chapter One, you are asked to mount platforms that move on your touch. You’ll ride these platforms one to another until you realize that you can use the momentum of these platforms to fling yourself far distances into clinging walls far offscreen. You’ll need to start doing this. Eventually you’ll be grasping onto the ledge of a wall far beyond what you previously thought you could reach in one jump. The base mechanics always remain the same—it is the mountain who changes to frustrate you, to play with and against you.

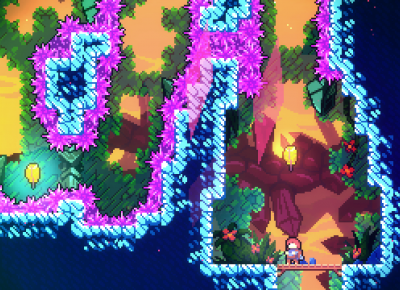

As you explore the mountain as Madeline, you find a mysterious mirror. When you look into your reflection, the reflection takes you by surprise and passes into your own world, dressed in purple and red. She tells you that she is “Part of You” and begins to chase you, and so begins a section where this Part of You follows every move you make and will kill you, and so the time to internalize a challenge and execute is drastically cut. This person, this part of you, whatever it is, would probably be the closest thing the game has to an antagonist, and Celeste’s greatest strength is that it never explicitly defines what this Part of You actually is.

There are many clues. Though at first Part of You seems like an easy cast as “Evil Madeline,” it soon becomes clear that Part of You is not something you can defeat nor leave behind. She challenges you when you assert that she represents the broken part of you, and though she is cruel, she is not some imagined brokenness that can be fixed. At one point after almost a half hour of dashing and clinging to your life, you call your mother and let her know you’re okay. She congratulates you on making it as far as you have, which is not a lot. She also asks you if you’ve been having any panic attacks. You lie. No, you’re fine, and you can continue on without help. I recognized myself in Madeline’s reluctance to ask for help, in her insistence that she would be fine—be happy again—if she could just do this one thing.

This is more than just a metaphor about overcoming a difficult task. This is about reckoning with your own behaviors, the parts of yourself you’ve chosen to neglect over time. Often those behaviors stem from concepts we have agreed on as almost universally frustrating or bad, like anxiety or depression, but there can be many neglected parts of ourselves, things that can be surprising—we criticize ourselves, we overwork, we struggle with taking a sturdy hold on an identity. For a game about a young girl climbing a mountain, Celeste is surprisingly less a coming-of-age story and more a story about how hard it is to take the tremendous first steps towards better health.

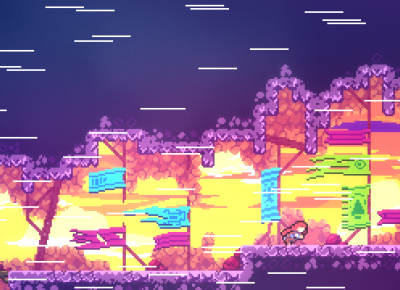

Purposefully, there will be points when you consider giving up, whether the next step is worth it, whether the peak is still worth chasing. It’s okay to question this goal, and the game will keep pace with your change in motivations as you and Madeline learn to better navigate the obstacles the mountain throws at you. The difficulty increases and you’re asked to keep up with it. Even when basic, critical-path challenges seem impossible, you’ll find offshoot rooms with completely optional strawberries to collect. As your ability catches up to your capability, you will better understand why you feel challenged. You will stumble less often but feel gratitude.

Celeste knows when to be brilliant and when to hush. It will cheer you on and pull you down. It understands that we all experience the illness of the world in different ways, that the mountains we climb are incredibly personal and that our attempts to fix them easily frustrate us. Celeste challenges not only the player’s reflexes, but her willingness to continue in the face of inward adversity. –Parker Scott Mortensen