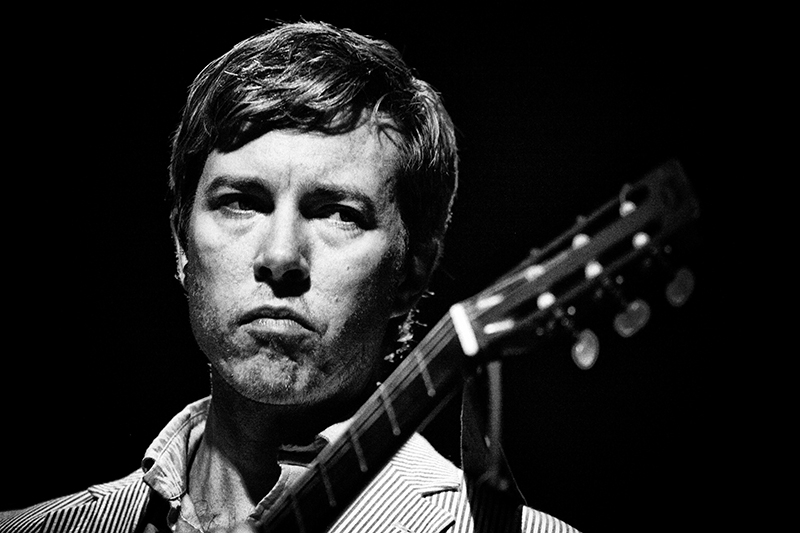

Bill Callahan @ The State Room 11.23 with Judson Claiborne

Show Reviews

The State Room is starting to annoy me. It’s not the venue (it’s a wonderful venue, a former theater, originally a furniture store, it’s got local history and great atmosphere and sound), it’s a number of the people who go there. Hipsters are here—a part of our time, so accept it, much like in earlier decades when grunge and “slackers” were the musical denizens. The State Room is just seeming like the habitat of the self-satisfied, self-important hipster—the kind that brags about their good taste in everything from music to microbrews. That’s just my perception, from more than one occasion.

Opener Judson Claiborne is more than a bit mysterious. Olympia, Washington singer-songwriter Christopher Salveter performs under the J.C. name sometimes with band mates, or in this case, solo. He seemed at times to be using the lyric notebook of Beck, with all its surreal linguistic and cultural juxtapositions, to channel the spirit of Jeff Buckley. “I’m drunk on American dreams, high on Canadian drugs,” he crooned in “Suffer the Human,” and that lyric seemed to presage a night of music based on American dreaming, as well as a critical brow cocked at the country.

One awkward moment: he asked if everyone was in town for the TPP protest, and no one seemed to know what that was at first. Ah, Utahns’ political savvy. He started to explain what it was, asked if anyone had gone to the protest, and finally I said I had. He had just opened for Callahan the night before in Boise, and he said he knew Callahan’s band was special, and he finally figured out why. He explained: it was what he imagined the female orgasm was like. This had to be the best teaser for a band in recorded history.

Judson Claiborne’s new full-length, We Have Doors You Need Not Keys, on In Store Recordings and La Societe Expeditionnaire, includes the single “Neo Pagan Love Song,” which he performed and was a highlight. He also performed a song by Buckley’s folksinger father Tim: “Once I Was a Soldier,” and this music drew on a tradition of folk music in a very educated, entertaining, non-trivial way. He sang a song about “a cat named Walter, who gave himself completely to a dead leaf in November,” and his songs were about giving yourself over, emotionally, and his voice was hypnotizing, seductive—it could get you to give yourself over to the moment. In “Gonna Beg You To Stay,” he created images of longing with languid vocal phrasing and legato guitar strumming, and the audience, if not begging him to stay, would find another performance soon welcome.

Bill Callahan seems like the minimalist indie songwriter par excellence, letting his lyrics, often more spoken than sung, work their dry yet poetic magic, but on stage with a full band, you realize that they are capable of a much more deep and uncanny array of tricks. They surprised from the get-go, opening with a cover of the Velvet Underground’s “White Light/White Heat,” in tribute of the recently departed Lou Reed. Callahan is perhaps the only singer who could deliver the lines more dryly than Reed. Then the band launched into “The Sing,” the opener from Callahan’s new release, Dream River (Drag City). “We’re all looking for a means to make one sing,” he states, and his musical mode is evocative, rather than declarative. The images in his lyrics, while often plain and unelaborate, are poetic in an American way: rich in metaphor and meaning.

His music sometimes takes a political bent: “America” from his last album, Apocalypse, was a touchstone of the show. The band transitioned from more straight-ahead folk rock and country twang-influenced sounds to effect-laden guitar work—even strangely psychedelic—from lead guitarist Matt Kinsey, on top of an at-times faux disco beat in this song. With his deadpan delivery of American cultural tropes, the effect might be like the tongue-in-cheek, detached irony of David Byrne, but Callahan’s catalog is couched in the cold circumspection of a savage indictment: “Afghanistan, Vietnam, Iran, Native American America! Well, everyone’s allowed a past they don’t care to mention.” His anger is due to how much affection he has for the country, as in the song he also calls out musical comrades-in-arms George Jones, Kris Kristofferson and Johnny Cash. This mini musical tour de force included a guitar lick by Callahan that sounded like an off-kilter version of “Gimme That Old Time Religion” and Kinsey’s guitar quoting “Dr. Zhivago.”

Kinsey was just one element in an extraordinary subtle and expressive musical unit that was Callahan’s band. His offerings recalled the noisy, lo-fi sound of Callahan’s former band Smog, except much more smooth and graceful. Drummer Thor Harris played a smallish kit embellished with percussive devices that he employed to add expressive accents to songs in an expert manner, hitting just the right emotional notes.

Bill Callahan is so old-fashioned in some ways, from the way he introduced each band member during the next-to-last song, a cover of Percy Mayfield’s “Please Bring Me Somebody to Love,” and let them each take a solo, to saying, “Thanks, you’ve been a delightful audience.” Often he tentatively marched in place as he played guitar, and has a Midwestern-seeming (he’s actually from Maryland) calmness and quietude about him that makes it seem like the stage isn’t his natural habitat. At the same time, he has a kind of authority as a stage presence that makes you trust in the journey this band is going to take you on, to places you didn’t expect to be traveling, lyrically, sonically, emotionally. On “Too Many Birds” he sang “If you could/only/stop/your heart/beat/for/one heart/beat,” adding one part of the phrase each time. His art is one of accretion, where meaning builds up gradually.

Matt Kinsey’s guitar playing was a real pleasure among numerous pleasures listening to the band, as carefully blended as symphonic musicians. His playing was both tasteful and adventurous, working an array of effect pedals with tinges of jazz stylings, at times biting, at times lush, but never heavy-handed. I wondered how Claiborne’s orgasm comparison would play out, and I my best guess is it’s apt because the band is extremely subtle, takes you by surprise, is incredibly mysterious and overall, is ecstatic, in its own way. Here I was, expecting this flat-phrased, minimalist, somewhat awkward performer, judging from what I’d heard on recordings, and then the experience was this incredibly rich, nuanced, unorthodoxically expressive master of his own musical idiom that owes much and adds much to distinctively American modes of music.

At the end of their set, Callahan simply said “Thank you,” and the band left stage without an encore. Perhaps they were tired coming to the end of their tour the next Monday in Denver. Upon earlier mention of that, an audience member said “Utah is better,” to which Callahan quipped back, “you haven’t legalized it.” The lack of an encore might have been partly because of the audience, some of which were a little chatty during Claiborne’s set, and a group of girls right up front talking and texting all through the show. But to me, an encore didn’t feel needed. Does a poet or novelist, after a brilliant reading, come back for an encore?

In “Ride My Arrow,” his baldly stated opening line “I don’t ever want to die,” is so plain faced and honest that it just about floors you. “Is life a ride to ride, or a story to shape and confide/or chaos neatly denied?” Callahan’s songs are poems, with all the visual evocations, but also oftentimes like little short stories, in the narrative places they take the listener. “Do you know this arrow when it arches high/to meet the eagle in the sky?” The trajectory of his musical vision is awe-inspiring and exhilarating.