Music

Tyler Childers

Snipe Hunter

Hickman Holler Records/RCA

Street: 07.25.2025

Tyler Childers = The Highwaymen + Sturgill Simpson + John Prine

Imagine you’re visiting Appalachia, hiking through the wilderness for days until you come across a shack in the woods. Out back there emanates the soft glow of a fire and, carefully creeping, you spy a grizzled mountain man roasting some venison over the flames. He beckons you over. Attracted by the fire’s warmth and smell of the sweet fixins, you approach, and spend the night listening to his tales. First they’re about where he came from: a holler in eastern Kentucky, not far from the trail you’re on. You might think this phantom figure hasn’t traveled much farther than that secluded valley, or from where you now sit with him. So when he starts carrying on about far-off, exotic locales, like Australia and the Hindu temples of India, you find yourself having doubts. Either way, he can tell a story, and he finally reaches for a guitar. He can play too. You listen, learn, and wonder. If his stories aren’t real, how can he know so much?

This is what it feels like listening to Tyler Childers’ new album Snipe Hunter. Produced in its entirety by Rick Rubin, it has all the hallmarks of the legendary music guru’s ability to draw something more diverse out of the artists he works with. One relevant instance of this was when Rubin infamously worked with Johnny Cash on a box set of six albums, the American Recordings series, in the years before Cash’s death in 2003. On American IV: The Man Comes Around, Rubin suggested and produced Cash’s rendition of “Hurt” by Nine Inch Nails, which became a golden-throated farewell to the world — arguably more recognizable now than the original.

Childers is an unabashed devotee of outlaw country acts from the mid-to-late 20th century like Waylon Jennings and Cash. He even recruited Cash’s engineer David Ferguson to co-produce two of his most commercially successful albums, 2017’s Purgatory and 2019’s Country Squire, alongside Childers’ friend and fellow Kentuckian Sturgill Simpson. The stripped-down music video for the Snipe Hunter single “Oneida” was filmed in front of an old, rustic, log-cabin house that supposedly once belonged to Cash himself. Working with Rubin on this new offering must have hardly been a decision at all.

Together, Rubin and Childers embark on a musical snipe hunt taking you from the holler to the world and back again. Generally, the term snipe hunt refers to a meaningless quest. Snipes are notoriously hard to catch due to their inherent nonexistence, and the hunt for these mythical fowl tends to take initiates to strange territory. On certain tracks – particularly “Nose on the Grindstone” – Childers shows he is still very much connected to his roots. His characteristic, gravel-crunching country croon is sharper than ever. Meanwhile, Rubin backs him up on virtually every track with electrified, harmonically saturated walls of sound, distorting calliope organs and slide guitars with the rattling grace of a sonic magician. Tracks like “Eatin’ Big Time,” “Snipe Hunt” and “Watch Out” are pure electric. Only “Cuttin’ Teeth” has the buttery smoothness of prior offerings like “Feathered Indians” or “Universal Sound.”

But Childers expresses a gnawing sensation on “Getting to the Bottom,” as he tries “getting to the bottom of an angst hard-fought to learn.” Meanwhile, the tune “Poachers” calls back to a song and video from 2023, “In Your Love,” which tells the love story of two gay coal miners. “In Your Love” sure ruffled some feathers and lost Childers a few disgruntled fans when it came out, alienating those on the Morgan Wallen end of the country fandom spectrum. On “Poachers,” Childers rebukes the over-simplified perceptions that others, including his friends’ parents, have about him as a country artist. “I can hear ’em now talkin’, ah, God, it is scandalous / His Papaw’d be rollin’, I don’t know where he strayed.”

The album’s production adds layers to Childers’ already complex melodic structures. Building on what’s present in the moment is a creative tactic that Rubin relies on. He doesn’t want the artist to change; he wants them to look within themselves, just maybe somewhere they haven’t drawn from before. Thankfully, and in the words of Walt Whitman, Childers contains multitudes. His father was a real-life Kentucky coal miner, and his mother was an avid reader. She inspired him to dig into literature at a young age, and Childers says he credits Jack Kerouac for instilling an explorative attitude in him early on.

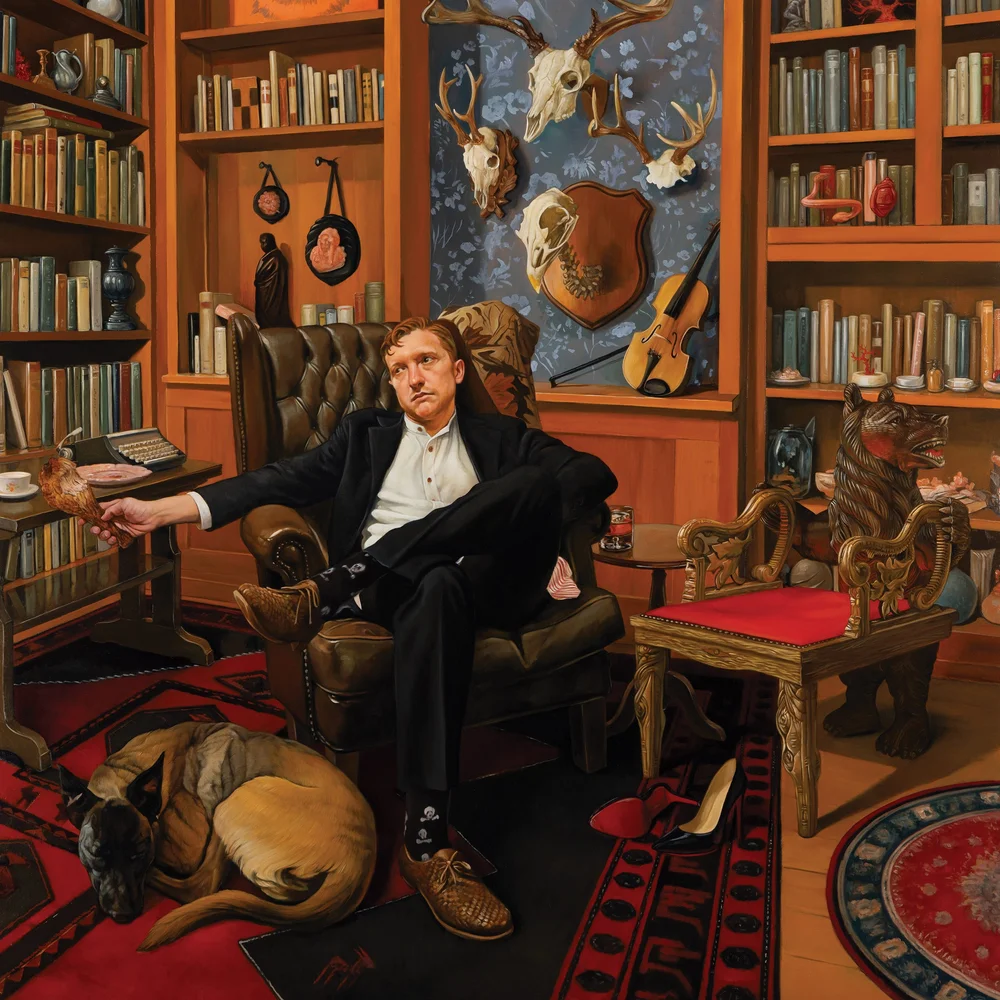

The cover art shows Childers in a woodsy study room filled with books. The room is an extension of himself, containing everything that he loves, from his fiddle to his dog, all hued in an Appalachian elegance. And while we can’t read the titles of the books, I’d venture a guess he’s got more than Mark Twain on those shelves. On “Tirtha Yatra,” a song about exploring the Hindu concept of Dharma, he sings: “I’d go to Kuru Sectura / You know I couldn’t even tell if I am or not pronouncin’ it right / But comin’ from a cousin lovin’ clubfoot somethin’ somethin’ backwoods searcher I would hope that you’d admire the try.” On my personal favorite track, “Tomcat and a Dandy,” he sings a hymn of love and death over a Hare Krishna mantra being chanted in the background.

Childers has come far from his roots while simultaneously remaining grounded in them. Now, after hearing all this, you get to decide whether this man, this grizzled phantom, mountain-humbug, cosmic “backwoods searcher,” is lying to you about where he’s been. It’s clear at least, from the earnest vocals to the honesty in his lyrics, that Childers sure isn’t lying to himself. —Kyle Forbush

Read more national reviews from SLUG here:

Review: Tyler, The Creator — Don’t Tap The Glass

Review: Hotline TNT — Raspberry Moon