Film Review: The End of Evangelion

Film Reviews

The End of Evangelion

Directors: Hideaki Anno and Kazuya Tsurumaki

Gainax Animation and Toei Company

Original Japanese Release: 07.19.97

Re-Release in US Theaters: 03.17.24

If you clicked on this review, you might be asking, “Why are you bothering to review this movie that came out nearly thirty years ago? Why now, SLUG? Why Evangelion?” So, before we get much further, to answer your question, I half-jokingly said we should review The End of Evangelion after rewatching it at my local Cinemark, and to my surprise, my editor actually said yes, so here we are. Now that that’s been established, I don’t expect this review to be an easy undertaking, with the story of Evangelion being… complex, to say the least, so forgive me for not trying very hard to lay out scene-by-scene just what happens. Additionally, the entire Evangelion IP has been analyzed to death (and rebirth) by many people much smarter than myself over the years, so I’m doubtful of my ability to contribute anything new to the conversation. At any rate, here goes nothing.

The End of Evangelion finds our 14-year-old Eva pilots reckoning with the end of the world, and whether or not they ever had a place in it. For the uninitiated, Evas are gigantic humanoid bioweapons and humanity’s last hope against the angels. These mechs can only be piloted by the aforementioned trio of preteens for a lot of reasons but in short—a psychic link. The angels, alternatively, are for the most part kaiju-esque creatures seemingly sent from heaven with the sole purpose of killing off humanity (with a few exceptions). After defeating a series of angels in the original Neon Genesis Evangelion TV show, the film picks up where the last of the angels are awoken to obliterate earth, per an ancient prophecy.

After getting his heart broken and being beaten into the pavement of near-insanity, our main character Shinji Ikari (Megumi Ogata) has given up on trying to save humanity and instead begs to be saved himself. Asuka Langley (Yuko Miyamura), our more fiery pilot, is at a physical and mental loss and unable to do much of anything whilst in a coma, and Rei Ayanami (Megumi Hayashibara), the most aloof of the bunch, is nowhere to be found. At the same time, NERV, the organization that keeps watch over the Evangelion program, has begun to reveal their sinister ulterior motives.

I first watched Neon Genesis Evangelion in the year 2015 when I was 14 and angsty. A funny coincidence, given that the series follows the plight of several angsty 14-year-olds in the year 2015. At the time, Eva had everything I wanted in a series. It was miserable and beautiful, hopeful and horrifying. Even while putting my former weeb nostalgia aside as much as I possibly can, I still found it sublime in the most metaphysical definition of the word. I still caught myself holding my breath while curled up in my luxury recliner. I still felt my eyes dry out as I tried not to blink.

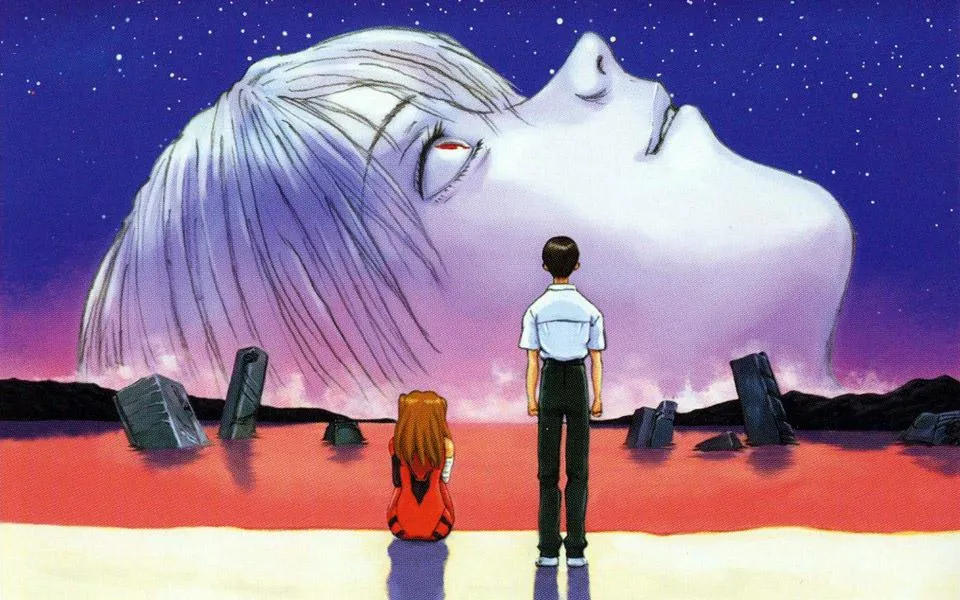

The easiest thing to admire about The End of Evangelion is its intense and visceral imagery. The film’s iconic style that you only see with the late ‘90s/early ’00s gets more cool as the years go by, picking up the same retro, sci-fi charm as The Matrix or, to name another anime, Cowboy Bebop. Additionally, Anno and Tsurumaki shock the audience with different styles of animation, and even bursts of live action that perfectly illustrate the unraveling of our characters and make for a visual experience that feels overstimulating in the best way. Though Tsurumaki has clarified in interviews that the notable religious symbolism in the show was purely aesthetically motivated and has little to no deeper meaning nor is meant to comment on Abrahamic faith, it still evokes strong emotion for those who grew up with it.

As gorgeous as it is to look at, thematically The End of Evangelion may be biting off more than it can chew. My own interpretation of the message of the original Eva series is to face your fears and live in reality instead of making up your own fantasies, a point that Shinji is explicitly told later in the film. Additionally, the film celebrates individuality and personal choice—unity at the expense of your own freedom being another guiding principle of the film’s philosophy. However, Eva also explores ideas like abandonment, love and the follies of puberty.

With all of this, along with the hectic chain of events that unfold in the film, “hard to follow” is an understatement. The film usually chooses to focus on the softer, more human elements of the film rather than explain what’s actually going on, which is fine if that’s what you watch Eva for. However, these segments can feel out of place when sandwiched between a military coupe and robot fight. I relish in this contrast, but I understand how it might throw some viewers for a loop. If you want to actually know the terminology and lore of End of Evangelion, it could take a few watches, which I think is worth doing. It feels shallow to criticize a film for being “too confusing,” but given that this has been a huge reason people choose not to engage with the franchise since its premiere, it still feels pertinent. Also, let’s just recognize that there are scenes and lines of dialogue that I wouldn’t say haven’t aged well, but more so that they were never really cool in the first place. You know which ones.

The End of Evangelion is one of the most influential animated films to come out of Japan, being parodied and referenced in other series and films for the past 27 years. Evangelion is a lot, but in a way, so is growing up. When I was 14, I didn’t really have to deal with a biblical sci-fi end-of-days situation, but that’s not to say I didn’t have my own problems. Looking back, I still think The End of Evangelion is worthwhile and while confusing, it’s also challenging and deeply human. Whether or not you’re ready to get into the robot, The End of Evangelion will likely endure for at least another 27 years and be waiting for you when you’re ready to face it. –Becca Ortmann

Read More Aesthetically Animated Reviews:

Orion and the Dark

Slide