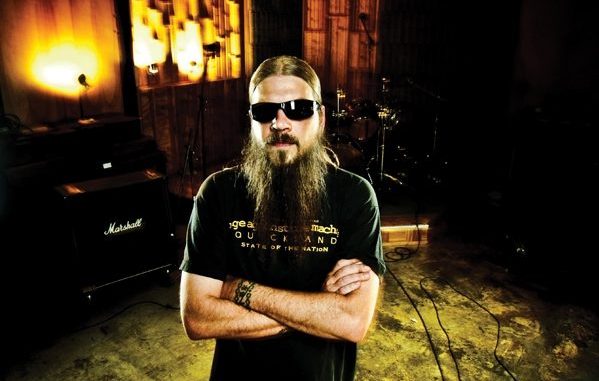

Andy Patterson

Community

Andy Patterson – In/Out:

Years Recording: 10

Studio Location: 3400 South 300 West

Studio Set Up: Pro Tools run through G3 Mac OS 9.1

Notable National Acts Recorded: DJ Shadow, Cut Chemist, Shelter, Ascend, Meg and Dia, Zach de la Rocha (narration)

Notable Local Acts Recorded: Red Bennies, Big Gun Baby, Mindstate, Julio Child, The Kill, Cub Country, Gaza

Back in the late 90s drummer Andy Patterson was looking to make it in LA. He placed an ad in The Recyler about his interest in joining a band and a woman responded. Patterson showed up to her apartment to talk about the group––instead Patterson ended up shaking hands with her roommate Critter (Jeff Knewel) and started an accidental mentor/student relationship that would later impact the Salt Lake music scene. Critter (former Ministry and Guns ‘N Roses engineer) taught the inquisitive Patterson about the Pro Tools rig that sat in the center of Critter’s living room.

Patterson took Critter’s advice to fuck engineering school and spent his savings on a Pro Tools rig instead. With the old-school engineer’s recording/editing advice bouncing around his head and a few months of Pro Tools experience under his belt in an LA studio where Blink 182 and Melvins tracking had been done, Patterson moved back to Salt Lake with his new skill set. He setup his first official studio space in the old KRCL studio space on 5th West.

There Patterson officially started his infamous recording career that led to nationally respected engineering work with over 250 bands. It was a perfectly setup skeleton for a recording studio and an ideal space until he was kicked out for being too loud during a recording session. Patterson took to the streets and found his current studio space off 3400 South and 300 West where he can be as loud as he wants, sometimes blowing three fuses at a time while harnessing monstrous amounts of electrically-fueled sound.

His current location is where bands like Blackhole and Cool Your Jets have recorded sessions between diverse acts ranging from SLAJO to Cub Country. Some might wonder at an engineer’s ability to record members of SLC’s straight edge scene and then push the “record” button on a pop record for Meg and Dia, but Patterson has played it all, so he can do it all. Patterson had a vibrant time in the 90s and 00s as a touring drummer with national acts in Europe and Japan with huge groups such as Shelter, State of the Nation, Blue Tip, Baby Gopal and Inside Out.

After drumming around the world Patterson started recording and using some of the same mantras he learned while on the road back in the studio. Cub Country’s Jeremy Chatelain confirms this “He’s punk rock to the bone. He’s a fast, no-bullshit engineer who’s interested in doing the best job he can with the cards he’s dealt in the studio.” Using creative solutions to curtail possible stumbling blocks, Patterson isn’t afraid to morph his studio in order to accommodate the specific needs of his clients: “One time, we were recording a friend’s vocals and she was super nervous,” local emcee Fisch of Julio Child and Rotten Musicians says, “Andy made like a mini-room and talked her through the recording process. After a while she was killing it.”

On a recent tour of his studio for SLUG Patterson recalled the kinds of rare incidents where he’s constructed temporary walls with at-hand textiles (bedsheets on those rare occasions). As we enter a large room with mismatched acoustic wall paneling he points at a cluttered closet made of glass: “This is a vocal booth, but it’s just storage. Honestly I just set up a mic right here,” Patterson points at the floor in front of the window into his production room.

“The only time I’ve built a booth is about four times and it’s usually just [a] singer being embarrassed because nobody can look at them,” he says. When he’s not building privacy blinds Patterson just sets up his microphone and records vocals ranging from operatic singing to whispering, and does it in the same room everything else is recorded in. Recording vocals outside of a booth is tantamount to blasphemy in some engineering circles. Patterson doesn’t give a fuck. He’ll build stuff to avoid a traditional method. It’s his method, even if it takes some extra work.

That extra-mile work really makes the records sizzle. So good you can hear it––listen to Ascend Ample Fire Within for confirmation. People might wonder how Patterson can get such awesome sound from his admittedly old-school gear, but he puts it this way: “The phrase in the audio community is ‘it’s not the gear, it’s the ear.’ You can have a guitar––same guitar, same amp, same pedals.

You have two different players [and] it will sound completely different.” Patterson says, “Having an assload of equipment doesn’t mean you’ll have good sound. I hope it’s because I make things sound good with my ears and not because of any equipment. It’s like cooking. Some people make a shit sandwich––another person makes a great sandwich, even when they have access to the same ingredients.” You can’t record hundreds of bands and not have a rep for being good. That’s what keeps Patterson working tirelessly as a producer/engineer.

Regarding that, Patterson would like to make a clarification on semantics and titles here: Engineer versus Producer. “They’re just titles and they do have connotations. People go to this producer because ‘he’s made awesome records and slick shit.’ A lot of the time they’re looking for that person to guide them.” Patterson says, “I consider an engineer to be more utility than coach––more like I’m making sure everything’s running OK––making sure the vibes all right.

But ultimately my job is technical over creative. The lines get blurred once in a while, but I think the connotation of producers is that I’m a guy in the couch on the back saying ‘No. That’s not the take. Do it again––this time with feeling,” Patterson says.

Continuing his explanation, Patterson repeats an analogy he’s made before, but one epically sized enough for reiteration, “I say that I’m the sherpa up The Mountain of Rock, but I’m not going to carry your backpack either,” Patterson says. “I’m not some grand dude that’s above it all. But what if a producer got a hold of a Hendrix nowadays? Or Janis Joplin nowadays? They’d be like ‘You don’t look the part. Your voice is too weird.’ We would have lost a lot of shit if people were producing in that regard. I think there’s a place for honest recording,” Patterson says.

Honesty in recording is a big thing for Patterson. He’s very much a purist in that regard. “There’s been discussions about different engineers in town and one thing comes up that I take defense to. Most people refer to me as ‘the laid back guy.’ Like I’m not going to say anything about your record, I’m just going to press record and I’m going to lay back, let you do your thing.” Patterson says, “There is some truth to that: I am mellow.

At the same time I’m respecting the idea that you are bringing your honest music to me that you want me to capture so other people can listen to it. Not ‘I’m going to bring my band in ‘cause we’re really awesome but we don’t practice.’ ” Patterson says, “and, ‘Why does it sound like shit?’ ‘Well, Andy was lazy and he didn’t make it sound good.’ I take defense to that because it’s not my job to make your music. My job is to capture your music and be helpful.”

Patterson doesn’t capture music 24/7, though his lengthy resume appears to make it so. In his spare time he watches flicks (horror being one of his preferred genres) with his wife Cindi and smokes meat on his grill, among other things. Smoking meat and watching movies about people becoming meat aside, one may still be wondering why? Why did the recording impetus even strike the late 90s era Patterson?

“I wanted my own voice. It’s because I’m a drummer and I’m at the mercy of whoever’s writing the songs. I wanted to take the power back so I made beats.” Moving from behind his kit and the making of beats in Acid Pro to a more behind the scene use of Pro Tools, Patterson started writing his own tale that has yet to reach its finale. But the rest of the story is out there building momentum: on CDs, vinyl and digital media all with Patterson’s impact on it, for better or worse—mostly better, though. Patterson agrees.

“I always tell everyone you’ll never find me complaining about anything because my life rules. I have a studio and I get to record awesome bands all the time. My wife works at a brewery [Utah Brewer’s Co-Op]. What the hell do I have to complain about?” Patterson asks. “I wish I made more money but that’s about it. I make enough to sustain so I can’t complain.”

Patterson is still sustaining and living his old dream of playing and recording music. He’s still drumming, with local band Iota (which recently played a SXSW showcase in Austin) and he’s also old-school enough that he loves working with tape when he can. He used to go to Counterpoint Studios to utilize their tape (analog) machine until it became outmoded and retired. He will still take bands there to record when they want “slick shit,” and he would love to branch out to their space eventually.

“I would love to work there and utilize their gear and their minds. I’ll figure it out somehow.” If that doesn’t work Patterson will still be plugging away in his own space into infinity, apparently. He will also be using his old Mac G4 and the Pro Tools rig he first bought in LA. Patterson says of his rig, “It is the same. I wouldn’t be keeping it real with the same gear if I had more money. By the time I’m in my 40s I’ll have great gear. But instead of buying a new microphone today I’m paying my bills so my electricity won’t turn off so I can record some more shit,” he says.

That’s because Patterson works on a shoestring to keep his costs inexpensive enough for most local bands to record with him, utilizing his ear and decades old experience to make honest music you have listened to, and will again, well after Patterson has reached his 40s. Looking around the studio with a reflective gaze Patterson closes by saying, “I still have this place after all these years so I’ve been able to pull it off where I didn’t fail in the first year. So somehow I keep it together almost in spite of myself.”