Progress Knot: Daniel Everett’s Cityscapes

Art

A city is like a knot: It can never fully be unraveled, but every tug on any loose end reveals something about the person trying. Daniel Everett is a Salt Lake–based photographer whose work has been featured at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA) and focuses on the way urban landscapes layer on top of each other, unraveling the sense of order and progress that city structures wield through their looming presence over our daily lives. Through his two projects, Vantage Point and Marker, Everett uses peculiar perspectives and crumbling façades to show a personal relationship to urban space.

Everett’s relationship with photography started during his youth as a way of processing the world around him. Photography made it possible to observe from a certain distance. “It gave me a kind of labor to perform when I wanted to disengage from interacting with others,” says Everett. This interest in isolation, of observing from an unobserved perch, feels like the keystone of his work. “Strangely enough, the images haven’t changed much from when I started as a kid,” he says.

On a fundamental level, Everett’s work has always been about expressing what it feels like to exist within a space, but the spaces he found most confounding were dense, urban environments—developed cities riddled with human-made structures and the architecture that sought to organize it all. The built environment challenged him to hone his expression.

“Strangely enough, the images haven’t changed much from when I started as a kid.”

For example, in 1999, Everett was working a retail job in New York City. “I would sometimes find myself alone in the subway stations while returning home,” he says. “There was something incredible to me about that empty, functional space. It was beautiful and terrifying all at once. Looking back, I think it was my first real experience with the sublime. I tried to make pictures of it at the time, but I just didn’t know how to do it properly. I think that’s what pushed me forward in art. I was trying to learn how to make images that did justice to the way these spaces felt to me.”

Across Everett’s work in Vantage Point and Marker, you can feel the artist’s distinct point of view. The images are gnarled and layered, and each body of work points toward a different method of processing the city. Vantage Point, comprises images of Tokyo and uses perspective to expose the way architecture layers over itself into angular textures, tessellating into urban tapestry. The foreground and background often bleed into each other.

Vantage Point came about as a collaborative project between Everett and the Swedish artist Mårten Lange, who approached Everett in 2016 after seeing that the two had made nearly identical images of an apartment building in eastern Tokyo. “I think I travel to Tokyo specifically seeking a sense of displacement and separate-ness,” says Everett. “Visually, I’m drawn to the organization of the city, but I think it also benefits my work to feel somewhat like a ghost.”

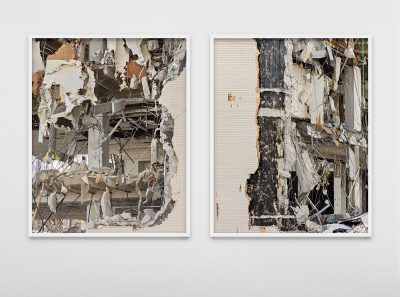

The images in Marker place the guts of progress center stage. Construction sites and unfinished demolition show the aesthetics of structures when they adapt and readapt to their own environment. “Over time, systems stack on top of systems and blur into one another,” says Everett. “I was interested in this cycle of things being added and removed in succession. To organize something is to make it disappear, and I was drawn to the elements that managed to remain.”

“Over time, systems stack on top of systems and blur into one another.”

Familiar, stoic structures become abstracted into unfamiliar, chaotic debris, and the work is legible thanks to Everett’s ability to make a visual vocabulary from rubble. The project started when Everett began collecting painted stones from construction sites. “They had been inadvertently sprayed while workers marked boundaries and then left behind when the jobs were completed. In the wake of progress, these stones remain as emblems of the organizational systems that displaced them.”

In some images, Everett digitally modifies the landscape to add more layers of visible attempts at reorganization, layers that originate from the observer and thus complicate the way we parse a given space. Reflections on a skyscraper become entry points for the bizarre. What does progress look like over time? Things that were once visionary, Everett says, tend to look pitiable in retrospect.

Taking in a city is a gargantuan task, and you could spend a lifetime finding ways to undo the knot. Sometimes Everett pulls a thread, and sometimes he cuts the knot in half—neither approach is a strictly favorable choice, but both offer an unfamiliar way to deconstruct the constructed. The artist is currently finalizing two photo books from these bodies of work, and a selection of Vantage Point images will soon be published in Foam Magazine out of Amsterdam. While COVID-19 has put anything else on hold, the artist is still at work with print-based projects, processing urban spaces in a moment when our relationship to them has never been more strained. You can see more images from Vantage Point, Marker and more on the artist’s website.