Utah Museum of Fine Arts: Reopen + Reenvision

Art

Since the building first opened over a decade and a half ago, the Utah Museum of Fine Arts (UMFA) is undergoing its most comprehensive permanent exhibition reinstallations. The museum has replaced the edifice’s vapor barrier and has switched out the UMFA’s signature guava-orange walls for a deeper palette of vibrant greens and blues. The South Asian collection has changed rooms, now situated near a dedicated Chinese art gallery. New on-view objects are showcased all throughout the expanded floor space of the permanent exhibitions, alongside Las Hermanas Iglesias’ interactive ACME Lab exhibition and Spencer Finch’s site-specific Great Hall installation, in which Finch circumnavigates the Great Salt Lake—using color. This Aug. 26 and 27, the UMFA will open its doors for a free two-day celebration of the museum’s reopening—and reenvisioning.

Since closing in January 2016, the museum renovations offered a chance for the UMFA curators to delve into and expand their permanent exhibitions, pulling out never-before-exhibited treasures and finding opportunities for the collection to grow. For Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art Whitney Tassie, that meant confronting and unpacking one particular phenomenon in art history, museums and beyond: representation. Shocked to discover the statistics compiled by Maura Reilly in a 2015 ArtNews article (i.e., only 7 percent of works on view in the Museum of Modern Art’s permanent collection were by women—in 2015), Tassie decided to take on Reilly’s challenge to “reconsider the hegemonic narrative of art history,” she says. She ventured into the UMFA’s permanent collection, anchored by two masterworks: Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Nets (1959) and Helen Frankenthaler’s Wizard (1963). For the UMFA’s new modern/contemporary installation, says Tassie, “I decided to show only work by women.”

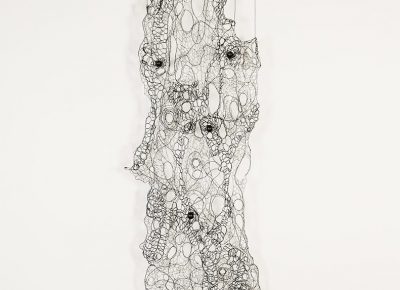

Located at the top of the museum stairs, each work in the new modern/contemporary installation is a masterpiece of the UMFA’s permanent collection. “It’s a pleasure to call attention to these artists,” says Tassie, pointing to the significance of pushing for increased representation in not only a museum’s traveling or temporary exhibitions, but also its permanent acquisitions. She notes the power behind Judith Whitney Godwin’s gestural brushwork and Signe Stuart’s experimentation with material and idea through sewn canvas and paint. Made from tire, Chakaia Booker’s striking Discarded Memories sculpture dynamically twists and jags, referencing both human skin and throwaway culture. Julianne Swartz’s intricate Lace Skin Tear lends an aural dimension to the installation: A layered, four-channel soundtrack eerily weaves through the gallery with tender words and sounds, spoken in several languages—foreign to some, familiar to others.

Plenty of local favorites are on show, too, including Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels, the beloved colors and lines of Anna Campbell Bliss, and Angela Ellsworth’s Seer Bonnets series, which references Mormon theology with bonnets made of pins—gorgeous and pearl-tipped on the outside, sharp and deadly within. Jann Haworth’s The White Charm Bracelet equips raw canvas—typically reserved for the “high art” of painting—for a soft, “laughingly large” charm bracelet, “a female form of storytelling,” says Tassie. “[Haworth] fits into the Pop Art movement, but expands it with a feminist narrative—something that was new to us, new to history.”

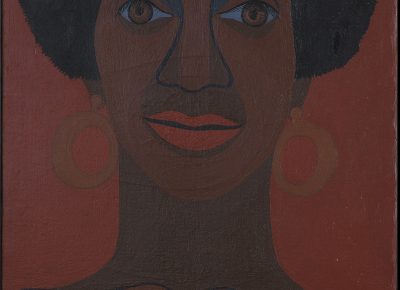

Refreshingly, the UMFA’s installation includes women-identifying artists from all around the world, representing a multitude of media, styles, cultures, time periods, art movements and experiences. On the easternmost wall of the modern/contemporary gallery are depictions of women by three artists of color. British-Ghanaian artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s hazy oil painting, Periphery, is a contemplative glimpse of a person in a light-blue dress, facing away from the viewer. New Zealander Yuki Kihara’s silent video, Siva in Motion, beautifully layers shots of the artist performing a Taualuga, a traditional Samoan dance. And in one of the UMFA’s newest acquisitions, Soul Sister (part of the artist’s Black Light Series), Faith Ringgold subverts her art school education, which only taught her to render skin tones with white pigment. Instead, Ringgold adds black pigment.

Noting the somewhat revisionist nature of the exhibition, Tassie welcomes the complexities that accompany discussions of gender, identity, race and representation. “I have to unpack that women weren’t allowed to study art, that women didn’t have access to studios and materials, let alone an audience,” she says. “I’m hoping this exhibition will help us to have these conversations, to unpack those ideas.” Part of unpacking those ideas is making the museum as accessible as possible, empowering visitors to have their own interpretations and interactions with the art. In the exhibition labels and didactic texts, Tassie asks the viewer plenty of questions, which range from the more pointed “Why do art museums own more art made by men than by women?” to the broader “Who can be a woman?” In addition to incorporating Spanish-language labels alongside English ones in select galleries, the UMFA has furnished three spaces throughout the museum for visitors to recharge, process and learn more. One of the spaces is a reading nook located on the balcony near the modern/contemporary gallery, and will offer videos, interviews and further reading, from Guerrilla Girls texts to Linda Nochlin’s seminal 1971 essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”

“We still have so much work to do,” says Tassie. “The priority, for me, is to have a collection that reflects the diversity of artmaking that is happening now.”

For more information, visit umfa.utah.edu.