Film Review: The Boy and the Heron

Film Reviews

The Boy and the Heron

Director: Hayao Miyazaki

GKIDS

In Theaters: 12.08

A siren sounds. A hospital burns. A young boy, Mahito (played by Luca Padovan in the English dub) is uprooted from Tokyo to the Japanese countryside. Hayao Miyazaki’s 12th animated feature, The Boy and the Heron opens on scenes of terror, bereavement and grief. In the 10 years since The Wind Rises was released, Miyazaki’s work has gained an inaccurate reputation for embodying an ideal of benign, aspirational coziness. While The Boy and the Heron’s opening minutes are certainly not an intentional rebuke to that notion, they are a striking and immediate reminder that as often as Miyazaki’s works are gentle and comforting, they are also thorny, complex and frightening.

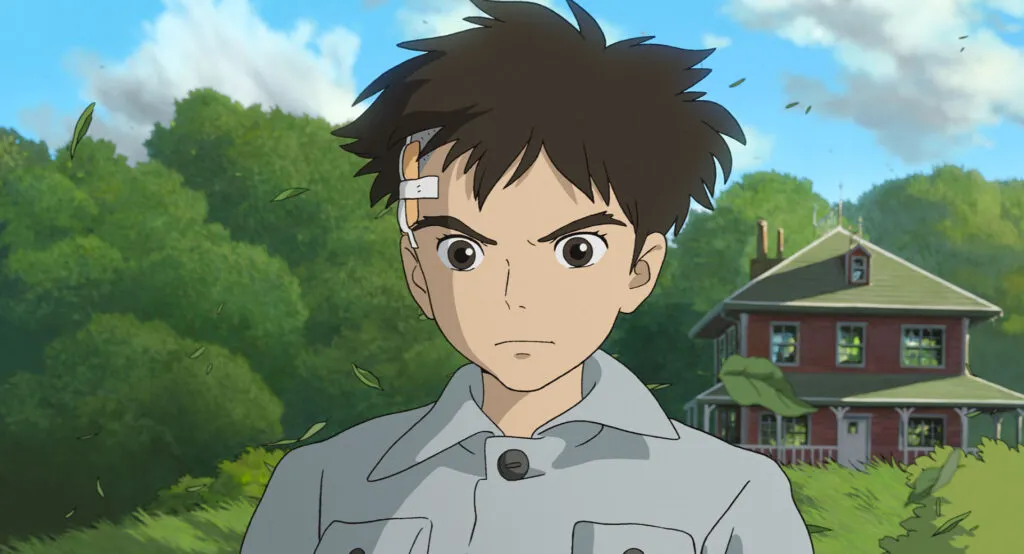

The Boy and the Heron plays like a companion piece to Spirited Away, Miyazaki’s previous otherworldly fantasy. Spirited Away is Miyazaki’s greatest showcase of his willingness to dive into the grotesque and macabre, a story spattered with blood, melancholy and filthy bath water. The Boy and the Heron is alternately joyful, funny and quietly moving, but it also breathes with similarly unsettling imagery and tones: Mahito is bedeviled throughout by several varieties of freakish birds. He is inconvenienced by frog mischief. He sustains a truly upsetting injury early in the film, the result of which is prominently visible from then on. I hope that, somewhere soon, a child will see The Boy and the Heron, and it will lodge its way into their young and vulnerable soul the way that Spirited Away did into mine 20 years ago. I hope the film frightens and haunts them and urges them to turn it over again and again in their mind and examine why the film might show them these things, what they might mean and why they are effective.

In contrast to the packed and restless bathhouse of Spirited Away, Mahito sinks into an empty and still world that’s rolling swiftly and smoothly toward the cliff of oblivion. Where Spirited Away’s Chihiro struggled to integrate herself into a community of thousands of unruly spirits, Mahito meets only a handful of other souls on his journey. He wanders at turns along the shore of a vast ocean and through barren and seemingly infinite landscapes of arches and warm light, reminiscent of the work of surrealist painter Giorgio de Chirico. There is a deep, eerie feeling that he has arrived at the end of something.

Miyazaki has often spoken on the ephemeral nature of his art and of Studio Ghibli, the animation studio he co-founded in 1985. “The future is clear,” he says in the 2013 documentary The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness. “It’s going to fall apart. I can already see it. What’s the use worrying? It’s inevitable.” Western media often interprets comments such as this as being cynical or even outright nihilistic. I think this interpretation is a misunderstanding that comes down to a difference in culture and perspective.

Miyazaki is an outspoken member of a creative culture that more readily accepts endings and concision as part of the natural cycle of things. Japanese comics, in contrast to most American comics’ never-ending relay of artists and ideas, are almost always created by a single author or creative team from conception to definitive end. Japanese homes commonly contain small shrines honoring deceased family members, the acknowledgement of death integrated into everyday life. When Miyazaki says that eventually Studio Ghibli’s time will come to an end, it’s because he knows that nothing, no matter how beautiful, benevolent or vital, lasts forever. That doesn’t make the work futile. It is the nature of endings to give meaning to what came before.

At its very heart, The Boy and the Heron is a story about endings and beginnings and how they are one and the same. It’s about the new things that can only grow in the ruins of the old. The film shows that it is exciting and vital to cut a new path ahead, but it is also necessary and honorable, at the end of that path, to step aside and leave the cutting to those who’ve come after you. In that moment it is a gift which only you can give, though it will be taken whether or not you give it freely.

Miyazaki’s art always observes and illustrates that there is beauty and emotion in every facet of life. Perhaps some of it is in the way a person picks up a feather or the way their eyelashes flutter in sleep. Some of it is locked in memories we cannot readily recall, in unexplainable tears and spontaneous laughter or in a comforting meal shared with a loved one. And some of it we will only know when we near the end of life and face forward into the greatest of all unknowns. With The Boy and the Heron, Miyazaki looks boldly and joyfully into that unknown and lets his audience know that it’s okay for us to go on ahead. –Daniel Kirkham

Read more reviews of Japanese animated films:

Film Review: The Red Turtle

Film Review: Danganronpa: The Animation