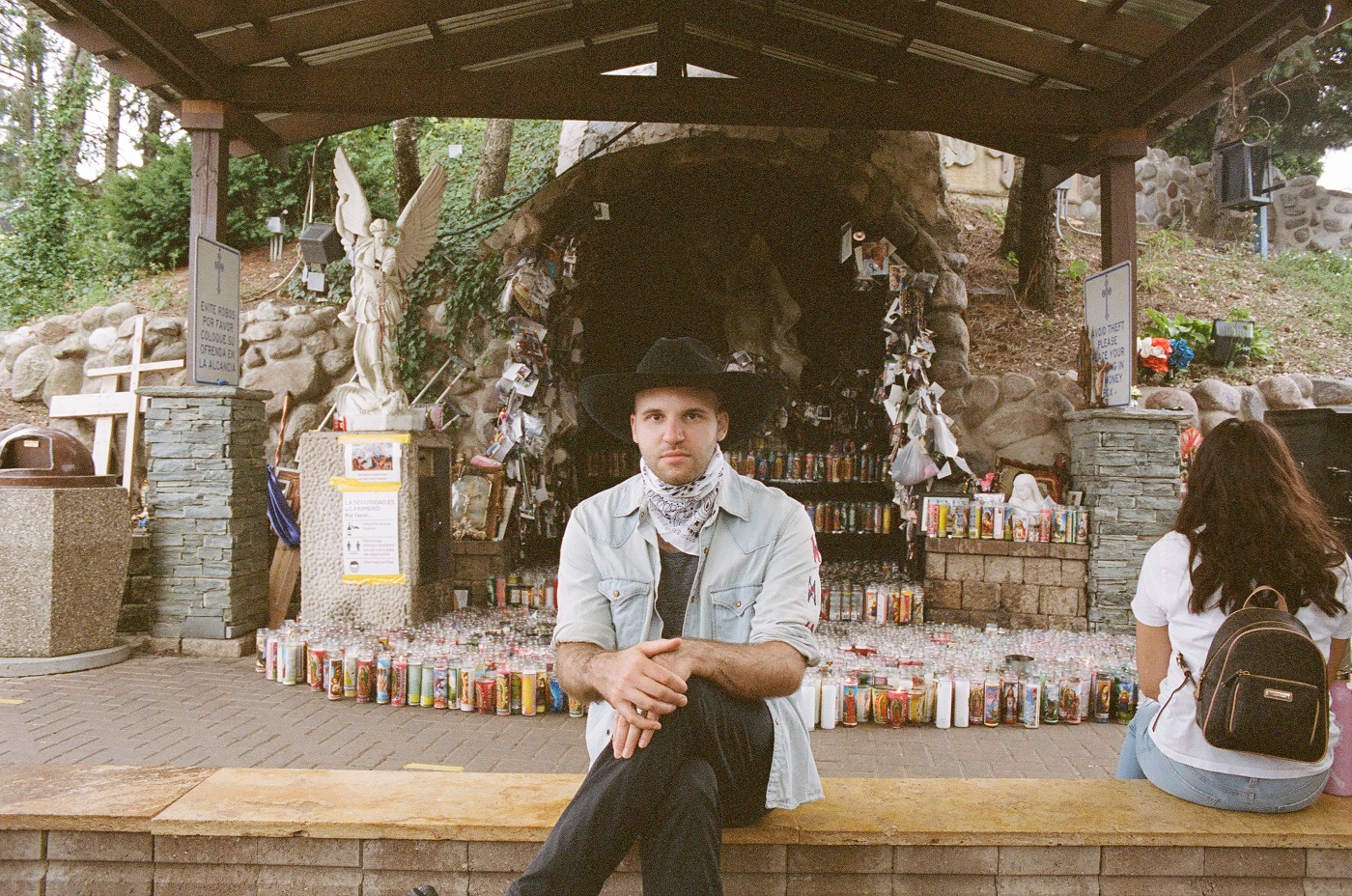

A Loving Cowboy: Jordan Reyes on Sand Like Stardust

Music Interviews

“Until I was 3 years old, I had this blanket that my grandmother or my mother gave me that was full of cowboy scenes. I would always be put to sleep in it,” says Jordan Reyes. For numerous reasons, this image holds a permanent locale in the composer, multi-instrumentalist, ONO member and American Dreams owner’s memory, and it serves as a pregnant signpost for the themes and sounds he explores on his new album, Sand Like Stardust. Through a cinematically sequenced set of Americana-leaning ambient and drone music, Reyes dismantles and reforms the myths of the American cowboy and charts a musical journey set to the cycles of rebirth and the passage of historical time.

The cowboy quilt from Reyes’ youth wasn’t a spare offshoot; rather, it serves as a single-item marker for a storied family identity. With a Tejano lineage in his extended family, the imagery, dress, lifestyles and lore of the cowboy was an early and omnipresent influence for Reyes. “The cowboy thing has always been in my family history,” he says. “My grandfather is a Mexican “dude” from San Antonio, [and] everyone wears cowboy boots on my dad’s side of the family,” a trait that Reyes has carried into his own fashion sense and has long shaped his vantage point in regards to the hijacked imagery present in the white American westerns of John Wayne and Clint Eastwood.

But the pull to incorporate these themes into Sand Like Stardust came first from a musical end; a desire to access the openness of folk music. “I was trying to show a connection between folk music and electronic music as a kind of democratic style of music,” he says. After toying with some modular synth–based interpretations of these ideas, Reyes turned instead to a purely analog framework focused on the physicality of performance and sound. “Playing something, really, or singing something … Even just vocalizing something was necessary. I think it has landed on the folk qualities,” he says.” The resultant album showcases plenty of singing, warm analog synths and keyboards, brittle country guitar lines and trombone drones, a grainy and tactile realization of this organic goal.

“I was trying to show a connection between folk music and electronic music as a kind of democratic style of music.”

When constructing these soundscapes, Reyes took on the inspirational lineage from Graham Parson’s concept of “Cosmic American Music” (a spiritual and fluid blend of blues, country, folk and rock n’ roll), so much so that the album’s working title was Cosmic American. As Reyes finalized the album and the greater picture of his artistic statement came into view, this title began to sour. Reyes found himself questioning whether such a close association could turn the album into “the thing I’m trying to work against,” he says, finding distaste in the phrases potentially whitewashed and nationalistic overtones.

Eventually, taking inspiration from one of his favorite authors (Samuel Delany and his Stars in My Pockets like Grains of Sand), Reyes settled on the new title, a more metaphoric phrasing that highlights the wonderous beauty of the open land and resists the pull of problematic tradition. “Even though it isn’t as up front and in your face about the influences of everything, it’s more true to the feeling I want to impart,” he says. “It’s more about the emotion of it, rather than the cold history.”

This approach centered on a new emotional connection with the land and American storytelling finds finds a potent distillation in the video for “Rebirth at Dusk,” directed by Eryka Dellenbach and featuring Reyes, fellow ONO members P. Michael Grego, travis and Connor Tomaka, as well as performance artist Ryan Greenlee. Accompanied by the track’s lackadaisical pinging guitar lines and its layered keyboard ambience, the short film runs through a series of impressionistic scenes that immediately reference traditional western imagery (the dress, desert-like sands, horses, etc.), but also subverts their original meanings through a conscious effort to highlight a more respectful, loving take on these recognizable tropes.

“It’s more about the emotion of it, rather than the cold history.”

In the film’s planning and execution, Reyes, Dellenbach and the actors wanted to turn away from the “indifferent and violent” attitudes held by colonialist cowboy fantasies. “The way that humans interact in this video is all positive,” Reyes says. “People aren’t taking away from each other. We’re all in this sort of symbiosis.” Of particular import was Dellenbach’s framing of the performers’ relationship to the natural world. “Eryka brought in this whole idea, this visual language of ecosensuality, which was like a communion with the earth, with the universe,” says Reyes. The director’s notes for the film further clarify this approach: “I felt inclined to imagine the cowboy as an ecosensual outsider, someone scrappy and magical with an amorous love of the land but who is reckoning with their identity’s legacy and ancestry.”

Though Reyes’ formal introduction ecosensuality dates after the Sand Like Stardust’s construction, the idea feels like an apt qualifier for the album’s music. In addition to the focus on analog sounds, the productions on Sand Like Stardust search for a nonhierarchical engagement with the physicality of sound and its makers—a similar “symbiosis” accessed through Dellanbach’s visuals. A key sound heard throughout is that of Reyes’ (somewhat) recently acquired ’50s lap steel guitar with a tricky habit of falling out of tune. “When they’re old, they can be temperamental,” he says of the instrument. “That’s sort of a charm—you have to wrangle that in.” Though never drifting fully into incidental microtonality, this autonomous pull holds sway throughout the album. On “High Noon,” the trebly swoops of the pedal steel provide a shaky foundation for the dust-drenched guitar melodies, giving the music a foreboding and unstable atmosphere.

As his personification of his lap steel suggests, Reyes sees these instruments not as tools, but instead an extension of and collaborators with the fickle beauty of the human body, arguably the main focus of the music on Sand Like Stardust. Of this relationship, Reyes says, “Everything that’s organic is temperamental. The human voice is temperamental. If you drink milk, your voice is gonna suck, so you don’t drink milk that day. Learning to take care of all sorts of organic instruments was a part of this process.” Like the amorous cowboys of the “Rebirth at Dusk” video, Reyes isn’t approaching these instruments with a mindset of taming. Rather, he seeks to coexist with his tones, working together to build natural atmospheres.

“People aren’t taking away from each other. We’re all in this sort of symbiosis.”

Fittingly, Reyes’ own voice appears prominently throughout Sand Like Stardust. Opener “Pre-Dawn Light” features a choir of Reyes’ multitracked singing stacked into monastic stoicism, a sacred chorale for a dawn that carries multiple significances. “What I tried to do from the beginning was to only use the first instrument that people could use,” he says. “I want[ed] this record to begin out of this void, this nothingness. Beginning with one voice that slowly becomes more voices.” Across the subsequent nine tracks, this ur-humanity expands into a day’s(year’s[life’s]) journey, through the metallic shimmer of “High Noon” to the unexpectedly menacing noise of “An Unkindness,” the the muted brass harmonies of “Rebirth at Dusk” giving way to the tear-inducing vocal hymn on “As the Sun Dips.”

And despite (or because of) the breadth of this journey, Sand Like Stardust closes with a note of glistening nostalgia and comfort. “Centaurus” arrives as a dreamy ambient update of the “Mockingbird” lullaby, an ode of eternal love made all the more affecting through Reyes’ baritone vocals and cushioned synth backdrops. Reyes sees this turn toward pastoral lullabies as the logical conclusion of a tumultuous path: “[It’s] beginning with something very serious, [then] spending your day as an adult,” he says. “But when you finish, you are still reverting to this place of vulnerability that, for me, I had as a child when I was being put down with this cowboy blanket.”

So perhaps instead of existing as a reframing of the Americanized mythos of cowboys and their western lands, Reyes uses Sand like Stardust to create a brand new story based on both age-old communalism and his own personal and family histories; an ever-evolving narrative where the allure of the wild west is founded on principles of love as opposed to ownership, where a return to childlike innocence stands as the welcome conclusion of a day’s work. “I was always a writer before I was a musician, really,” says Reyes. “And I was a storyteller before I was a writer. I just feel like the reason that I’m alive is to collect and tell stories. That’s the reason to exist. To channel the memories and expressions of people who aren’t there to do it.”