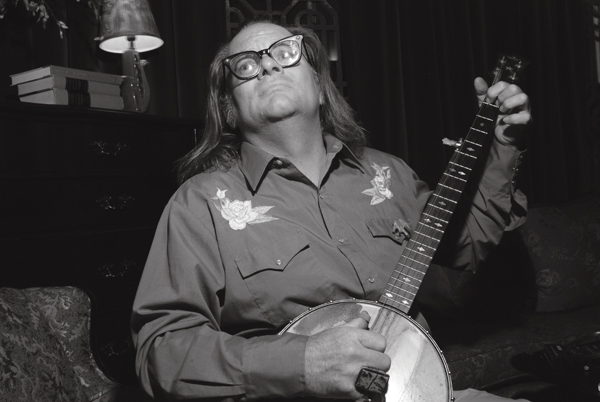

Bob Moss 1953 – 2011

Eulogies

Over the years, Bob Moss contributed to many SLUG projects. He designed the cover of SLUG’s 16th anniversary issue (Vol.16 Issue #194, Feb. 2005), translated and illustrated phrasing in the Deseret Alphabet for SLUG’s Death By Salt III local music compilation and released an exclusive track on the mag’s first Death by Salt complilation. In addition to these official projects, Bob would sporadically send SLUG Magazine handwritten letters and pieces of art he had been working on. Bob was a musical and visual art-folk genius. He will be missed by many, but never forgotten.

Bob Moss was the greatest man I’ve ever known.

At first he was just the hairy dude in a picture on my friend Brian Staker’s desk. One day, while awaiting my paycheck, I imagined him plunking off-key songs on his beat-up guitar. “That’s my friend Bob Moss,” Staker said. “He’s an artist and musician.”

I adore a freakshow, so I begged Staker to tell me Bob had a CD. Days later I held his copy of Bob’s Headjug CD, eyeballing the cover art.

A capsized, head-shaped jug lies between wavy words: “Bob Moss & the Westernmen” above and “Headjug with guest star Alvino Rey” below. An arrow points from “Headjug” to the actual jug. At left, peeking out from behind the jewel case’s clear plastic spine, is a column of exotic characters (later I’d realize it was the Deseret alphabet, an obsolete Mormon creation) in the same scrawl—Bob’s own hand, as it happened. The song titles foreshadowed a loony ride: “I Believe in Ghosts,” “Clowntown,” “NyQuil Habit.”

I was giddy, sure I’d discovered—in terms of incredibly strange music—the mother lode. I wanted to clap like a toddler and exclaim, as Bob’s song goes, “Oh Goody Goody.”

Inside are handwritten album credits and a tight spiral of thank-yous to “Toshiko Endo & her dog Buster,” “Elvis impersonators,” folksingers, bluesmen, jazz cats, sci-fi authors, comics, artists and friends. Bob misspelled many words, even his own song titles (“Nye Quill Habit”), which reinforced my assessment of him.

Except there was this music. At first Bob’s voice sounds kooky, and it doesn’t help that he’s singing about clowns, conspiracy theorists and cough syrup buzzes, either. (I still have contradictory urges—do I laugh or tremble—when he intones, “I take that NyQuil for an action-packed snooze.”) Headjug’s outsiderly charms beguiled me, but an understated instrumental virtuosity bubbled beneath.

Eventually, Staker brought in a piece of Bob’s folk art. It was a small piece of wood on which Bob had découpaged a photo of Bob Dylan and woodburned squiggly lines and Deseret characters. Visual art wasn’t my cup of tea then, but this odd plank captivated me.

A couple of years later I pitched a story on Bob to City Weekly. He invited me to visit his home in Clearfield—a small office in the storage facility he managed for his folks. He was as I expected: awkward, peculiar, unique. Mostly the latter. More importantly, he was hospitable and kind. Even as he evaluated your trustworthiness, he made you feel like a welcome friend.

That first visit revealed a Wonka-esque world. I saw his cluttered workspace in the corner of the office, abutting his bed, which was strewn with more colorful, be-glittered woodburnings as well as scattered folk LPs and letters in various states of completion. He showed me his bathroom, and pointed out Pollock-y splatters on his shower wall. “I open all my canned goods in here so it doesn’t get all over my stuff,” he said, proud of the practicality.

Outside, he raised the aluminum door to a storage unit, unveiling a Fort Knox of art and miscellany. In the bed of an old pickup truck were piles of raw art materials—acrylic paints, glitter, unsanded boards alongside stacks of finished pieces. Afterward, he sat patiently on the train tracks out back as I wrestled with light and composition, hoping to capture a photograph that did this man justice (at least as I knew him then).

He asked for a ride into Salt Lake—the first of many. As we drove, he wolfed down a plate of curry chicken and spoke of esoteric books and films, and friends like Toshi, an old Japanese woman he looked after. I thought how this man, who lived reclusively among massive clutter and disorganization, is who seemed to need a caretaker. Well, he did and he didn’t.

Bob was precisely who he wanted to be. He’d occasionally lament his lack of funds, but he was essentially satisfied. “I’d be happy with fifty bucks,” he once said. Such a modest sum, but he could stretch it forever, hunting bargains on art supplies, stamps, or the expired salad dressing he liked to pick up at the scratch-and-dent grocer. And somehow he found a way to give generously.

He wrote copious letters and often included return postage. Every year he’d send a small piece of art as a Christmas card. He offered to teach me to woodburn, and gave me scraps of leather and wood, or damaged gourds for practice. He even loaned out his treasured possessions.

I tried to give back. I started and, as time allowed, maintained his MySpace page, bought lunches, wrote articles, gave him promo CDs and images he might like to use in his art. It wasn’t enough. Bob Moss was the mother lode of friendship. In addition to volumes of peerless music and art, he left me with the urge to create more than I consume, to be kind, compassionate and grateful.

He wasn’t a freak—he was a true original. The greatest man I’ve ever known.