Comic Review: March 1993

Archived

Comic books, as a legitimate art form, have been enjoying a renaissance, especially with the development of the so-called “graphic novel.” Graphic novels are usually self-contained stories of unusual lengths (for comic books) and often employ more experimental techniques in art and story than in mainstream comics. Victor Gollancz Publishing, along with American co-publisher Dark Horse Comics, has published a number of ambitious graphic novels, three of which are reviewed in the following section.

Kling Klang Klatch

Written by Ian McDonald

Illustrated by David Lyttleton

Published by Orion Publishing Co.

Dark Horse Comics

“Kling Klang Klatch is set in a superficially glittering world that, if not exactly human, reflects humanity’s desires, corruption and racism at a fundamental level,” so reads the back cover blurb for a wickedly thoughtful and entertaining excursion in comic book form, Kling Klang Klatch.

This remarkable tale begins in Toyland, a reality in which toys live and breathe in a setting much like that found in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (and yes, I realize that film is based on a Philip K. Dick novel. The reference here is to Scott’s vision of a steamy, rainy, high-technology Raymond Chandler-esque dystopia.). The affable but grumpy inspector McBear is disturbed by police dispatch and finds himself in seamy PandaTown, investigating the apparent homicide (or, in this case, ursicide) of one Ling-Ling Moe.

The truth to this case is much more disturbing as McBear finds evidence implicating the mysterious Kling Klang Klatch and suggests that forces within the police themselves may be responsible.

This is a fascinating reading, but there is more below the surface as the description implies. McDonald, best known for work in the sci-fi genre, sets out to weave a morality play that is savage but insightful, without resorting to preachiness. As McBear uncovers details, the reader is exposed to the workings of Toyland, and Toyland’s passions and foibles prove to be remarkably like many of our own. Service robots threaten strikes. The rich flaunt their impunity. Segments of the population are treated as lesser beings. Addictions to substances are revealed.

McDonald manages to combine these elements with a sharp wit and satirical edge that enables the work to function at several levels. Luckily, McDonald is matched in his virtuosity by illustrator Lyttleton.

Lyttleton’s distinctive look infuses the story with power. Combining equal parts whimsy with grittiness and outrageousness, the pages speak volumes. Perhaps the only detraction to Kling Klang Klatch is a momentary lapse by McDonald in which he and Lyttleton actually appear in several scenes. The cleverness of this is lost on this reviewer and these panels prove annoying. That said, Kling Klang Klatch is a very impressive foray by two newcomers to the sequential art format, and one that should prove entertaining (and maybe enlightening) for comics fans and non-fans alike. Maybe mainstream comics creators should take a tip from McDonald and Lyttleton. Grade: B+

Minotaur’s Tale

Written and Illustrated by Al Davison

Published by UG Graphic/Dark Horse comics

The often nasty manner in which humans with “deformities” and “disabilities” are treated by society is the meat for Davison’s latest creation, Minotaur’s Tale.

This often moving, modern-day fable begins with a re-telling of the Greek myth of the minotaur, seen from the minotaur’s vantage point. Davison then moves on to modern-day London, where an unfortunate soul nicknamed Banshee is beaten by punks (and one feels a need to pick on creator Davison for abusing the punk stereotype for his own convenience).

Banshee awakens in a hospital room where he is astonished to himself the object of the kindness a young woman, Etty Mae Brown, and the attention of Doctor Sparks, who is troubled by her own “affliction.” It’s Etty who sends Banshee of self-reflection. as she present to him: the diary of the minotaur.

As Banshee discovers the behind this myth, the reader is drawn into an emotional world of turmoil and is faced with questions of what makes something so beautiful or ugly. Is the surface reality or perhaps inner world in which beauty truly exists? Conundrums such as self worth and empowering the individual are also considered as Banshee find himself finally believing in his own inner beauty and worthiness of love.

This description may make this tale seem heavy-handed, but it never stoops to that level. Creator Al Davison knows his material, while having overcome the challenge of spina bifida to contribute his talent to contemporary theatre and comic books. Indeed this seemingly simple story provokes powerful emotional responses as Banshee’s inner journey is interwoven with the Minotaur’s life story. Just as the Minotaur discovers that he deserves to be loved, so does Banshee, in a satisfying and denouement.

All this is to Davison’s credit, but the work is nearly sabotaged at points by the artwork, which moves from classical Greek-type illustration to realism to outright and annoying cartooniness. Banshee’s appearance, in particular, is so jarringly exaggerated at points that the parallels stand out in an uncomfortable way. Luckily, the power behind the narrative manages to cover up these flaws.

The Minotaur’s Tale is remarkable in its ability to convey a message of importance to today’s surface and exterior-obsessed humans. Al Davison should be commended for creating a work of such beauty which challenges society’s faulty notions. Would that all comic books were so noble in their scope (color $11.95) Grade: B

Signal To Noise

Written by Neil Gaiman

Illustrated by David McKean

Published by UG Graphics/Dark Horse Comics

The very creation of art through ideas (the evolution of signal to noise is the coux of Signal To Noise, the latest of talented comic book writer Neil Gaiman and artist Dave McKean.

Well, maybe that’s not entirely true, but Signal To Noise tells the story of the evolution of a 50 year old London director’s last film. Only the filmmaker knows this work will never be finished because he has terminal cancer. So Messrs. Gaiman and McKean takes us along on an inner voyage through the director’s head, navigating past self-denial to inevitable self-acceptance. As he snaps out the vision for the story of a tiny European village waiting for the Apocalypse on the last minute of the last day of 999 AD, his life comes into focus for achievements and single-minded focus.

Well, maybe that’s not entirely true, but Signal To Noise tells the story of the evolution of a 50 year old London director’s last film. Only the filmmaker knows this work will never be finished because he has terminal cancer. So Messrs. Gaiman and McKean takes us along on an inner voyage through the director’s head, navigating past self-denial to inevitable self-acceptance. As he snaps out the vision for the story of a tiny European village waiting for the Apocalypse on the last minute of the last day of 999 AD, his life comes into focus for achievements and single-minded focus.

Is there more to life? One could hardly expect to learn these things from a “mere” comic book. Or might one expect more?

Fortunately, writer Gaiman leaves the dialogue ambiguous, abandoning the reader to his/her own mind to dig below the surface. As usual, Gaiman crafts a powerful narrative with realistic dialogue and wonderfully obscure references.

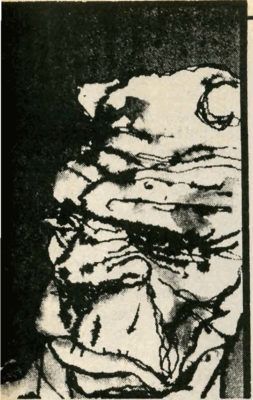

But artist Dave McKean may surpass Gaiman in his mixed media and imaging techniques. Combining realistic, and wild, hellish visions, McKean convinces the reader of the concrete reality of what is occurring while depicting the inner reality of the director. The resulting combination of text and pictures leads to a vision that is nearly religious in its sweep …

Profound, depressing, witty… Signal To Noise is all this and more. Creators Gaiman and McKean should be applauded for daring to punish the limits of graphic storytelling. Maybe when sales for work like Signal To Noise exceed those on super-hero fare, the large comics companies will wise up to the potential of the medium … (Artist David McKean is also the genius behind Tundra’s 10-part series Cages, one of the most innovative comics found and well-worth searching out.) (color $11.95) Grade: A-

Check out more from the SLUG Archives:

Comic Reviews: February 1993

Comic Reviews: January 1993