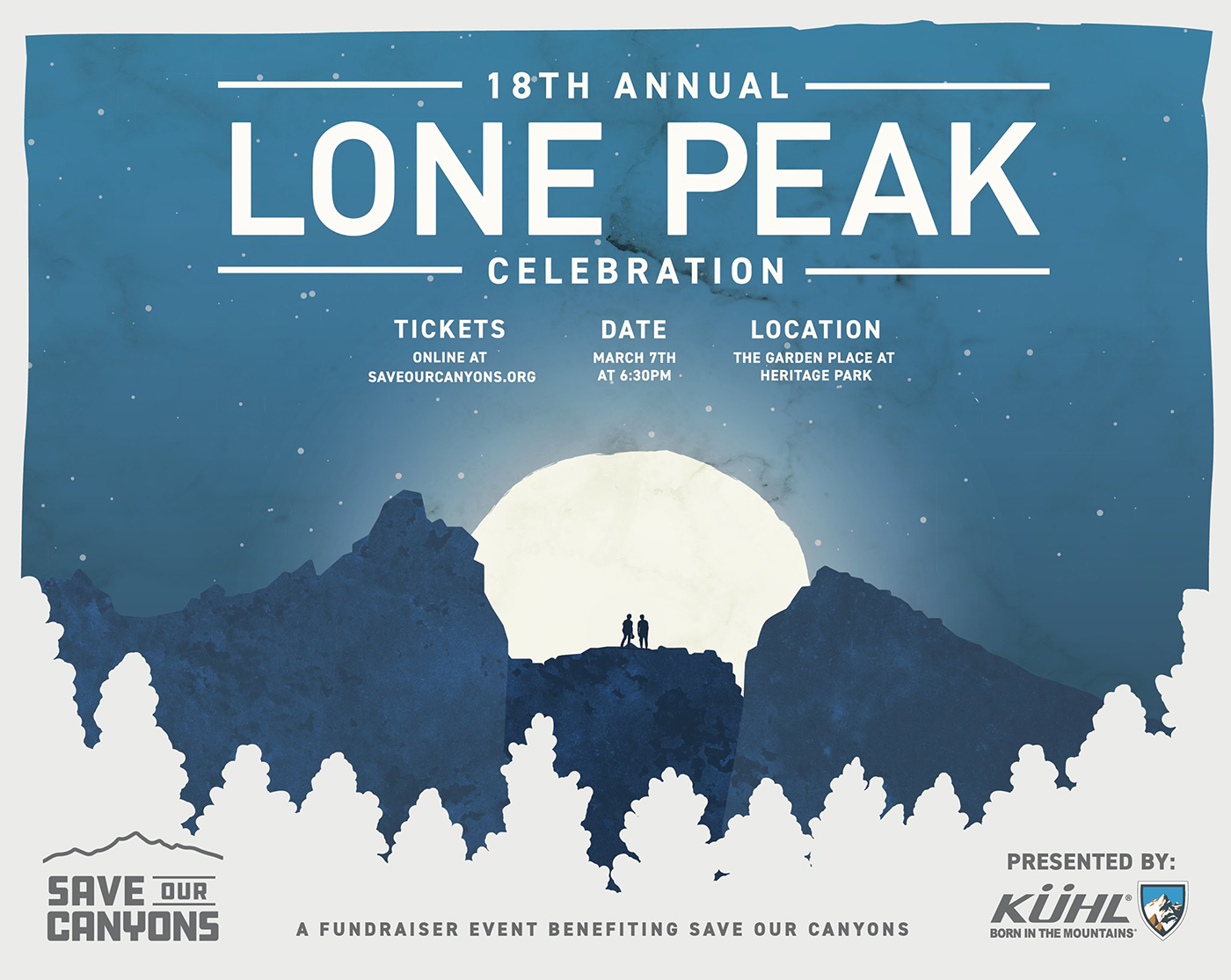

Rally Around the Wasatch: the Save Our Canyons 18th Annual Lone Peak Celebration

SLUGmag

In 1978, Salt Lake City–based non-profit Save Our Canyons successfully contributed their efforts to the creation of Utah’s first-ever designated Wilderness area. The celebration that ensued was named after the newly protected area: Lone Peak Wilderness. Wilderness in Utah was realized, and so was the organization’s annual fund-raising benefit: the Save Our Canyons Lone Peak Celebration.

This year’s event was held in The Garden Place at Heritage Park, a swanky, barn-esque venue supported by impressive joinery and gigantic golden timbers. As people poured in through the entryway wearing various forms of “mountain casual” attire, a cheerful string band conjured a jovial atmosphere. Right away, the room filled with the classy, conversational energy of a gala, which combined nicely with the casual vibe of going for a hike with friends. As a non-profit “dedicated to protecting the beauty and wildness of the Wasatch canyons, mountains, and foothills,” Save Our Canyons wisely selected a loosely defined dress code. Footwear on display ranged from sandals to Gucci loafers to Vans. Had the organization decided to go with Black Tie, many of these public lands-supporting conservationists may have been left scratching their heads and staring blankly into their closets—and that’s a compliment.

“This year’s event was held in The Garden Place at Heritage Park, a swanky, barn-esque venue supported by impressive joinery and gigantic golden timbers.”

Between colorful puffy jackets and the silent auction offerings, which mostly included accessories for outdoor recreation, the supporters of Save Our Canyons made clear that they have some deeply shared values. These are the kind of people whose care for the wellbeing of the natural spaces around them is a focal point of their identity. Some of the people attending the fundraiser likely moved to Salt Lake City for the unparalleled access to outdoor recreation and aesthetic beauty. Others perhaps were born and raised here and find themselves passionate about keeping urbanization at bay and preserving the place they have known. A slideshow on a large screen at the front of the room displayed the glorious Wasatch in her various sunlit and snow covered forms. An activist brand of empowered pride of place united the room.

As the crowd swelled, a lengthy queue awaiting their turn at the bar began to wrap around the room. The drink menu featured earthy cocktails made with local spirits from Dented Brick and Bee Hive Distilling. For any ski-bro types in attendance, Montucky Cold Snacks were also an option. Another major attraction was the silent auction. Tables covered in items and bidding clipboards were swarmed as Save Our Canyons supporters perused with interest. Clothing company KÜHL, the event’s “Summit Sponsor,” contributed a wide variety of pants and jackets to the collection. Most of the trinkets and toys in the auction were donated by local businesses and artisans. Tasty catering from Mazza was served as people settled into seats, preparing to listen to an address from Executive Director Carl Fisher.

“These are the kind of people whose care for the wellbeing of the natural spaces around them is a focal point of their identity.”

For four-plus decades, Save Our Canyons has been a consistently active stakeholder in local decision-making processes regarding our immediate environment. While Utah was vying for an Olympic bid in the ’70s, Save Our Canyons worked to keep new sporting venues out of environmentally sensitive areas. In 1989, the organization influenced Salt Lake County to adopt a guide for granting building permits on both public and private land in the Cottonwood canyons. More recently, a proposal to roll back “the Roadless Rule” would have opened up millions of forested acres to development of roadways in Utah. Save Our Canyons fought and succeeded in defeating this proposal. During Fisher’s speech however, past victories were not the primary focus. Instead, Fisher spoke definitively about the numerous issues that are threatening the vitality of the Wasatch today.

Fisher asked the crowd to raise their hands if they have been stuck in a traffic jam in one of the cottonwood canyons during this year’s ski season. Hands shot into the air as Fisher transitioned into the topic of transportation. “I don’t want to see a completely built out and developed Wasatch,” he said, referring to proposals to build complex transportation options within the canyons. Save Our Canyons’ position on this issue was laid out plainly: “We simply need to start running busses.” Fisher then briefly addressed inclusivity, which has been a criticism of proposed transit plans for the canyons. Important to the transportation vision is a grid of bus routes that would provide access to the canyons from all parts of the city, including those neighborhoods that are historically marginalized and underrepresented. “We need to connect all of our communities to our canyons without building more crap in these mountains,” said Fisher.

“I don’t want to see a completely built out and developed Wasatch.”

Save Our Canyons juggles many ongoing efforts. A wilderness stewardship program maintains trails and high-traffic recreation areas utilizing volunteer effort. The organization’s education program brought hundreds of low-income students from Title 1 schools into the Wasatch in 2019.

The 18th Annual Lone Peak Celebration assembled a like-minded congregation. As indicated by the healthy turnout of over 200 and the ample supply of donations from local businesses, Save Our Canyons is moving forward with a sturdy bedrock of support. For those that share a connection to the environmental integrity of the Wasatch Range, Save Our Canyons can be considered a dynamic leadership force. Fisher summed up the nonprofit’s existence at the conclusion of his speech: “We will fight for the legacy we want to leave behind in the Wasatch.”