Review: Norco

Game Reviews

Sometimes home is what kills you. There comes a point where the parameters that defined you are now suffocating. How can you become a real person when the life that brought you here is so tied to a place and time? There are a few answers to this, and one of them is to leave. Norco, the point-and-click game from Geography of Robots, depicts a southern-gothic reality that tugs at how for-profit industry has irrevocably fucked us—and how we find ourselves picking up the pieces.

In Norco, you play as Kay, a person who has returned home after what feels like a lifetime of living away. The experience of traveling across America has taught you much, imparted a sense of the world you once dreamed of knowing, but the reality of your return is harsh. Your mother, who suffered from cancer, has died, leaving your brother Blake with a house mere blocks from the oil refinery where your father also died several years ago. Kay returns to Norco, Louisiana (a real place, though only census-designated) because home is where you go when the pain reaches a certain point.

Blake, Kay’s brother, is missing. A mystery! There are people to ask and places to visit. Surely he must have been at the bar—or did he make his way to the convenience store for smokes? None of the Norco regulars know where Blake is. Eventually you discover Blake has fallen in with the Garretts, a cell of disenfranchised boys who dress like Best Buy employees and insist society is to blame for their woes. Garretts are sad, rejected boys who don’t fit in with the hipster crowd and were excluded by the punks. From this rejection they have found a savior, Kenner John, a figure eager to franchise lost boys into labor. To be a Garrett is a sad but empowering reality, fueled by its discontent. Blake needs rescue from this line of thought.

Norco is replete with rumination on this circumstance. Your mother’s death is sad and inevitable, and your brother’s reaction is predictable and just as sad. He has rejected society, but in doing so he has reinforced its worst contours. Norco is a place where disenfranchised boys slurp Code Red and watch too much hentai. They say reprehensible things and knowingly follow a fraught calling.

But you left Norco for other reasons. You are someone who, for whatever reason, was not welcome in Louisiana, and your absence and experience has stripped you of your identity, experiencing much but leaving you impressionable and looming in adolescent limbo, waiting for something or someone to impress upon you the conditions for self actualization. Norco is a game for people who once left home and eventually found something worth returning to. The sad realism will be familiar to the depressed, to those who see through shallow calls for optimism.

Central to Norco’s plot is the oil company Shield (a play on Shell Oil), who has priced out regular people from living near the Mississippi River by gouging the land of resources and life and then buying it up once its actions render the land undesirable and cheap. Shield is a local stand-in for industry at large, for the unnecessary destruction of life that fuels a higher class. We know it well, and we call it the names it asks us to call it (Norco is an acronym for New Orleans Refinery Company). Shield offers recognition, power, comfort and little else beyond a mandated minimum wage and healthcare. It sucks life from the land and gives birth to viruses beyond current comprehension. Norco envisions how the subsequent disease may be embodied in the years to come.

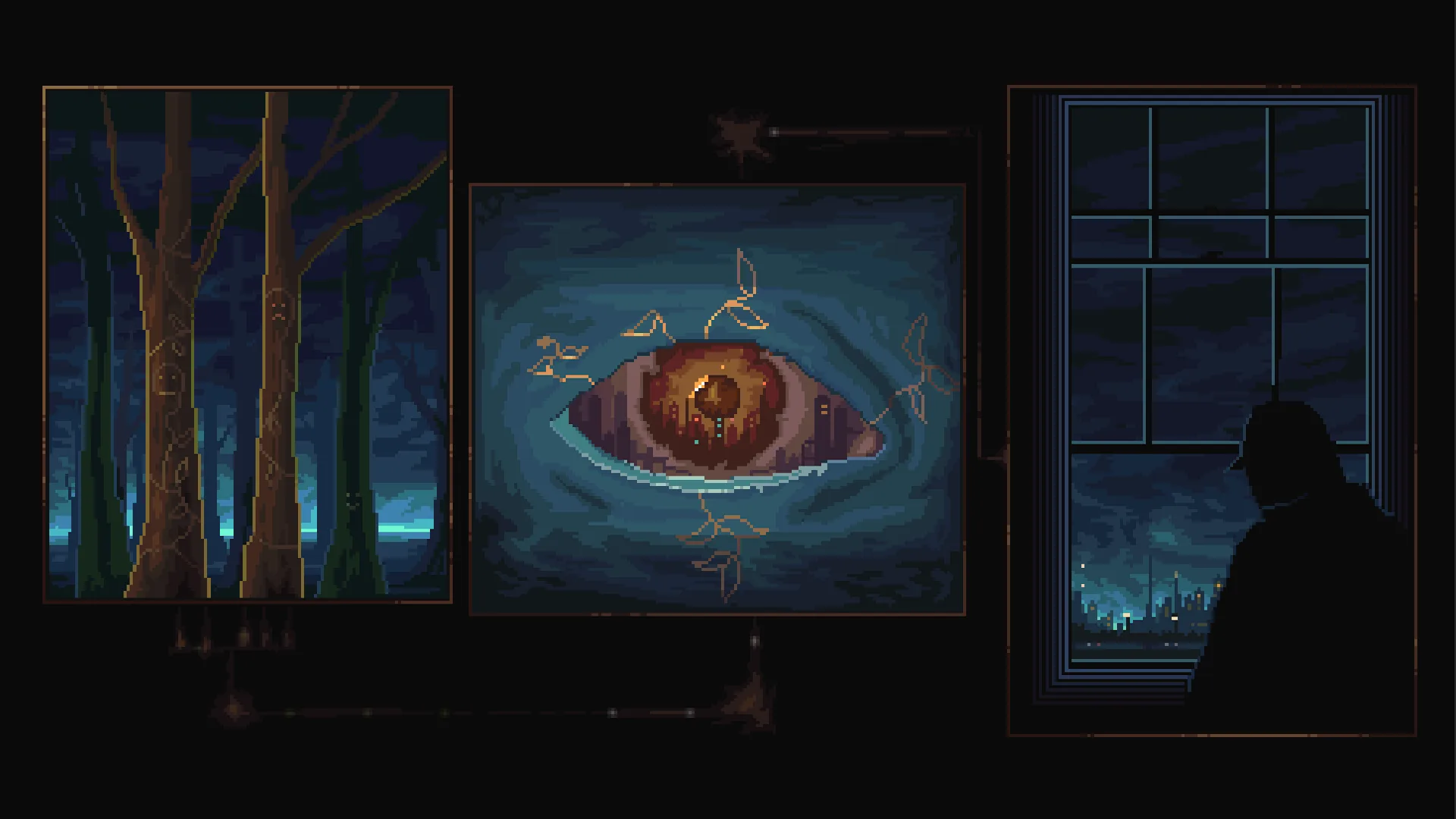

Metaphor quickly becomes reality in Norco, and it begins so grounded that the transition between familiar reality and a broken future may happen so naturally you might not notice. For the better, I’d say, as there is little benefit to thinking of Norco’s depiction of rural, industrialized life as pure fiction. –Parker Scott Mortensen