The Angle of Light: Black Refractions

Art

Through April 10, the Utah Museum of Fine Arts is hosting Black Refractions: Highlights from the Studio Museum in Harlem. This exhibit surveys nearly a century of work by artists of African descent, featuring 100 works from 80 artists. Black Refractions speaks to the wide range of experiences that constitute how Blackness exists in our country while also giving the opportunity for Black people to see their individual, affective experiences refracted onto canvas. Meligha Garfield, Director of the University of Utah’s Black Cultural Center partnered with UMFA in the programming and outreach for this exhibit and appreciates the scope of the show: “Global Blackness is so incredibly diverse, and I think this exhibit showcases that,” he says. “I also love that it’s from Harlem, being a New York native myself.”

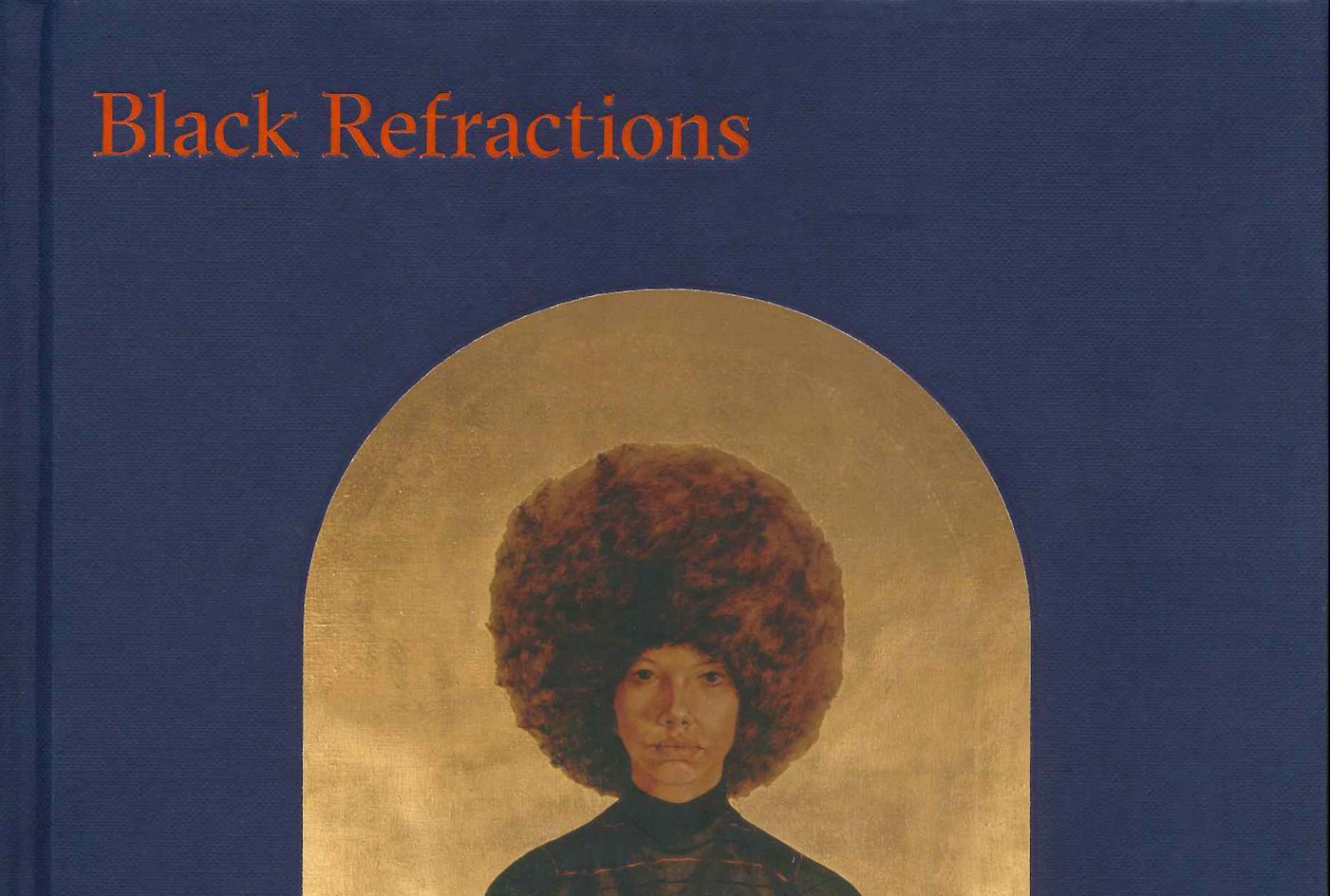

The Studio Museum in Harlem, who owns the Black Refractions collection, aims for—and indeed is known for—catalyzing and promoting work from artists of African descent. Founded in 1968, the studio was conceived at the height of the civil rights and Black Power movements and uses Lawdy Mama, an oil and gold leaf on canvas by Barkley L. Hendricks from 1969, as its key art. The figure’s afro, enriched by the gold leaf underneath it, is both dark and vibrant. It beckons toward the era in which the Studio Museum began and its goal of fostering safe social forums for communities and artists to view and interpret art together. The safety of such a physical forum is something we may have taken for granted in this present day before public gatherings became limited—now the opportunity to engage with such a collection imparts a renewed sense of privilege.

“The aims of the Studio Museum in Harlem and the U’s Black Cultural Center coalesce in this collection.”

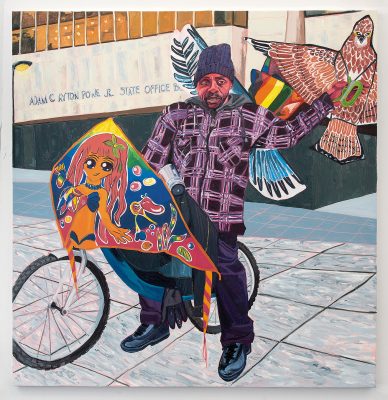

For Garfield, Jordan Casteel’s Kevin the Kiteman hits home. In the piece, Kevin sits on a bicycle decked in kites of various kinds—hawks, wings, rainbows, an anime mermaid. Behind him is a state office building engraved with and named after Adam Clayton Powell Jr., the first African American to be elected from New York to Congress. “An amazing feat,” Garfield says, “but based upon the missing letters in his name, this symbolizes what’s often the neglect and disregard for preserving Black history and culture in this country.”

Garfield sees his own history in Kevin, both as a Black person and as someone from New York. “When growing up in Rochester, I often felt the city was consistently in between seasons,” he says. “We were always on the verge of something great, but not quite there. We wanted the big city feel of New York City but did not want its population density or taxes. We wanted to be a cultural hub but disenfranchised those who brought it. The man in this piece signals that with his winter clothes and kites that are often associated with the spring season. In a way, he’s a walking contradiction.

“I would also say the man in this artwork represents a piece of me: someone who grew up poor in the inner city of grey skies and organized crisis,” Garfield says. That phrase—organized crisis—sticks out to me. The aims of the Studio Museum in Harlem and the U’s Black Cultural Center—to catalyze the careers of artists of African descent, to fight global anti-Blackness and to generally strengthen the connections of the African diaspora—coalesce in this collection.

“I’m reminded that to someone else, that perspective will be familiar, personal.”

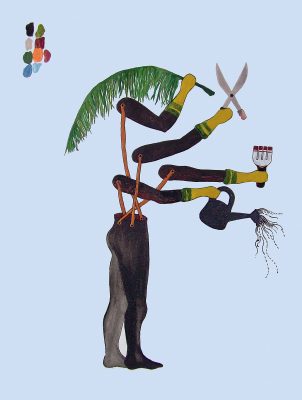

Otobong Nkanga’s House Boy, a 2004 watercolor, ink and acrylic on paper work, struck me through its commentary on Black bodies as a source of house labor. The lower body stands intact and acts as a grounding stake not for the upper body but for the four mechanical arms, each holding a garden implement. It’s a stripped-down, functional imagining of the body. What you might see as overbearing social commentary in modern sci-fi or cyberpunk as here finds strength in its specificity and focus on the instrumentalization that Black bodies have actually experienced.

My favorite piece is Mickalene Thomas’ Panthera. Made of rhinestones on acrylic, a black and purple panther lays in a soupy heat, surrounded by branches that drip with blue-and-pink tatters. The panther’s teeth and face, almost human-like, register an uncomfortably familiar sense of fatigue and warmth. With the way purple rhinestones bleed from the landscape into the panther, the whole image feels as though it exists from a perspective I’ve never seen before. I’m reminded that to someone else, that perspective will be familiar, personal.

Black Refractions will be on display at the UMFA through April 10, 2021, though visiting hours have changed (and are subject to change). Currently, the museum is open Wed. 10 a.m.–8 p.m. and Thurs.–Sat. 10 a.m.–5 p.m. The 10a.m.–11 a.m. hour is reserved for seniors and high-risk individuals. To help prevent the spread of COVID-19, gallery capacity will be limited, and visitors are required to reserve tickets in advance at umfa.utah.edu/visit.